April 26, 2017

Demonstrated Harm

Cuts to School Funding are Hurting Virginia Classrooms

Reduced state investment in public schools in Virginia since the recession has significantly impacted day-to-day operations in schools all over the Commonwealth. Schools have been forced to eliminate teachers and instructional specialists, place increasing responsibilities on teachers, reduce critical support positions such as nurses and school counselors, not keep pace with the changing language needs of students, eliminate student clubs and shorten afterschool programs, and allow facilities to deteriorate and fall into disrepair.

To balance the budget during the recession, state lawmakers made significant, ongoing cuts to state support for public schools. Local school divisions have tried to absorb these cuts — which amount to 11 percent per student since 2009 adjusting for inflation — yet they have had to make hard choices in managing their own unique challenges.

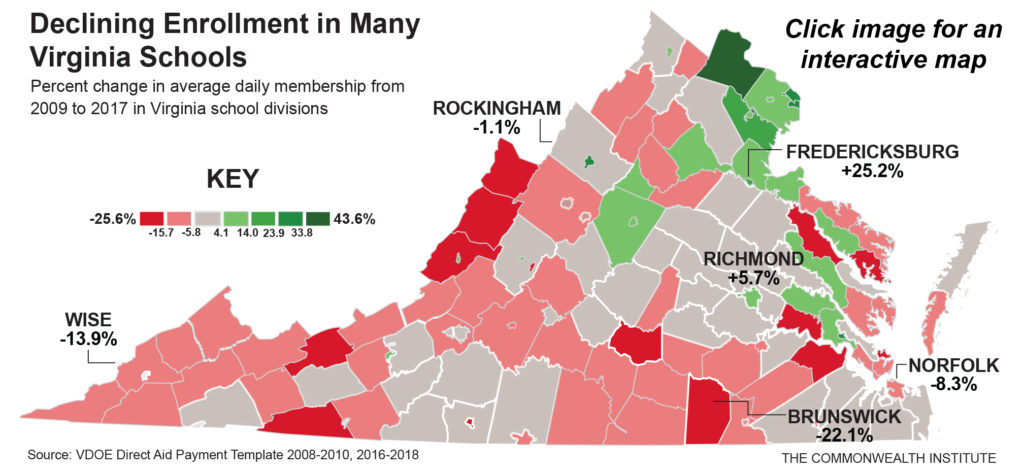

Schools in southwest and southside Virginia have also had to manage declining student enrollment — equal to over 20 percent since 2009 in some divisions — that has compounded state per pupil cuts and made it difficult to manage large, aging facilities. Meanwhile, many areas have experienced changing student needs and schools have struggled to adapt with limited resources. For example, areas in Northern Virginia, Greater Richmond, and the Hampton Roads region have seen large increases in the number of English learners requiring language specialists that schools have been unable to find or afford. Similarly, some areas have also had large increases in economically disadvantaged students that can require additional counseling and one-on-one classroom attention that schools have struggled to provide.

Every student in Virginia deserves a fair shot at success in the classroom and after they graduate. And Virginia’s economy demands a future workforce that is prepared with the skills, knowledge, and competencies to help make it thrive.

The Commonwealth Institute conducted focus groups in six school divisions during the summer and fall of 2016 across the state. The purpose of the focus groups was to gain understanding of the key challenges and opportunities facing school divisions from the perspective of on-the-ground teachers and administrators.

This report summarizes the findings from those focus groups and features experiences from educators and administrators from all over the state to better understand the array of challenges Virginia schools face. The focus groups were conducted in Brunswick County, Fredericksburg City, Norfolk City, Richmond City, Rockingham County, and Wise County. This mix represents different geographic areas of the state, both urban and rural communities, and both growing and shrinking school divisions.

In the Classroom: Fewer teachers, larger classes, outdated resources

Fewer Teachers and Instructional Specialists

Teachers and other instructors make up a large proportion of school employees — about two-thirds of school staff in Virginia — and this makes it hard for schools to balance their

budgets without looking to cut back on these positions. And unfortunately, many schools have made that difficult decision to

cut back on instructors.

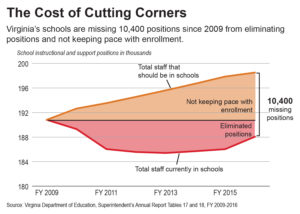

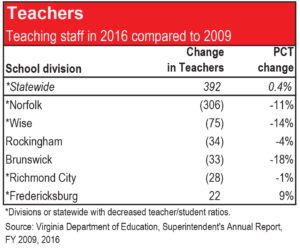

Statewide, staffing in Virginia schools has not kept pace with growing student enrollment since 2009. If they had, there would be over 4,200 more teachers and instructors in classrooms guiding students. Schools all over the state have been forced to tighten their belt on instruction. Most of the school divisions visited for this report reduced their overall teaching staff. For example, Norfolk has 306 fewer teachers and Wise has 75 fewer teachers. Only Fredericksburg has been able to increase their teaching staff, but even that has not kept pace with their rate of enrollment growth.

All told, Virginia public schools have about 2,800 fewer staff than in 2009, including teachers, counselors, principals, and support positions. If schools had kept pace with growing enrollment there would be 10,400 more staff instructing students and making sure schools run smoothly.

These staffing reductions have had impacts in classrooms. A Brunswick school administrator explained, “every time that the state actually cuts back, we have to cut back on personnel and staff…Before the recession actually hit, you had teachers for everything…And now, it’s down to pretty much the bare minimum. Every time a teacher retires or something of that nature, then the position is actually cut.”

Some of these classrooms that see multiple long-term substitutes in a year also have high percentages of low-income students with instability of their own in their home life. One teacher noted “when you have unstable teach[ing] in the classroom too it just creates even more problems.”

In addition to regular classroom teachers, some administrators and teachers identified that resource positions for subjects such as reading, math, and science are among the positions that have been eliminated in their school divisions. For example, since the 2008-2009 school year, Brunswick County schools has eliminated three of their twelve instructional support positions.

In Wise, one teacher explained that her school used to have a reading resource teacher who helped students with remedial reading. “We don’t have that [position] anymore,” she said. “That was cut.” Another Wise County teacher explained, “60 percent of our students are [at] at-risk reading levels” and that makes reading intervention positions like literacy coaches or resource teaching ‘incredibly valuable.’”

In Norfolk, science and social studies resource teachers that had provided supplementary instruction are instead teaching regular classes. One teacher explained, “Those specialists are now going back into the classroom when we need them to do individualized work with kids,” said one teacher. “Kids aren’t getting as many resources on a consistent basis as they should be getting.”

When asked how the elimination of teaching positions has impacted their students, one Norfolk teacher said, “look at our tests scores.” The elementary school that lost the science and social studies resource teachers has since had large declines in their SOL pass rates in these subjects. Their declines far exceed statewide decreases that many schools experienced as the state increased the rigor of certain SOL exams. For example, the percentage of students passing the 5th grade science SOL in this Norfolk elementary school has fallen 32 percent since 2009, while statewide pass rates on this exam have only declined 8 percent.

Larger class sizes

Cutting instructional positions can result in larger class sizes which research shows can have harmful effects on student learning outcomes and performance. This is particularly true for students from low-income families. Many schools in Virginia have extremely high concentrations of these students. These schools have the greatest need for keeping class sizes low. Yet, staffing reductions have increased class sizes in some schools to difficult and unmanageable sizes.

The number of students per teacher is increasing in places like Richmond City, where 38 percent of school-aged children live in poverty — that’s an income under $25,000 for a family of four — and 74 percent qualify for free or reduced price lunch. The ratio is also increasing in Norfolk and Wise where over one quarter of school-aged children are living in poverty and 60 percent or over qualify for free or reduced price lunch. The impacts are being felt in the classroom.

One Wise County teacher explained, “We’re running 30-31 [students] in classes now [compared to] the 20-25 we use to have…In my school, last year, we only had four seventh grade teachers [for] 120 kids.” He later added, “We don’t have the money to replace the [teachers].”

Likewise, in Norfolk, “Staffing is an issue,” said one administrator. “In urban environments…children most benefit when the numbers are smaller [in the classroom] …Our class size numbers are huge. [There are] 30-35 [students] in our core subjects…The recession and the cuts from the state have really resulted in us having higher class sizes and it is very difficult for teachers to meet the needs of students with those numbers…Norfolk is an excellent training ground. But we are losing the best teachers to surrounding districts because of things like class size.”

Recruiting and Retention Challenges

State cuts have also meant that local school divisions have fewer resources to put towards increasing teacher pay. Since 2008, the state has only contributed two times to pay their share of a teacher pay raise. The result is that Virginia is one of the worst in the nation when it comes to the competitiveness of teacher salaries. In 2014, the average teacher salary in Virginia was $49,800, compared to $56,600 nationwide. That’s 12 percent below the nationwide average. The Education Law Center ranks Virginia 46th out of 50 states and DC in competitiveness of teacher salaries — this measure compares the salary of teachers to other occupations in the same labor market and of similar age and degree level.

Lagging teacher pay has made recruitment and retention a real challenge for school divisions. Teachers in Norfolk, Brunswick, and Fredericksburg all discussed challenges recruiting and retaining teachers.

In Fredericksburg, one teacher suggested, “Most teachers that are in this system are here as dedicated people. But dedication can go but so far.” She continued on to say, “We lose our staff mainly to Stafford, Prince William, and Fairfax.” The average teacher salary in Fredericksburg ranges from $1,700 to $13,300 below these neighboring divisions. The teacher continued “as well as we try to do, we are not retaining people…In general, people leave for better pay. And it’s not the dedication…It’s about livelihood, and trying to rear a family, and trying to pay your bills.”

One Norfolk teacher suggested that things like teacher pay, “[Have] become a teacher retention problem.” He explained that, “Being at a six year level, I am a rarity. You see one year, two year, or three year teachers and then you see 20-25, and there’s no in between…The state funding has just not been able to help the city maintain and pay teachers a respectable amount where they don’t feel that they need to go back to school, change careers, or move to a different district.”

Outdated Textbooks and Insufficient Technology

The school divisions with large per-pupil cuts from the state report not having access to essential instructional resources such as computers, up-to-date books, or modern instructional tools like Smart Boards. These challenges in particular were raised by focus groups in Richmond City, Norfolk, Wise, and Brunswick.

One Norfolk teacher explained that in her middle school, not only are their social studies books falling apart, they “don’t correlate to the SOL.” Similarly, a Richmond City teacher said that one of the content areas in her school would not be getting books until November, two months after the start of the school year. As a result she says, “our basic instructional materials aren’t even in the building…And that is if you get to order [books]…Our students have textbooks that date all the way back to 1998.” Another teacher indicated some textbooks date back even further. For teachers without access to quality textbooks, bringing in outside material can be essential to enhancing lessons. Yet, several Norfolk teachers noted that they are only given a monthly allowance of 500 copies, which they find inadequate for providing students with the relevant and accessible learning materials.

Financial strain due to decreased state support has also made it difficult for some public schools to provide their teachers and students with the technological resources they need in the classroom.

A Brunswick County teacher explained, “We have 21st century learners…and, a lot of the classrooms still don’t have Promethean or Smart Boards. And so with math, there are a lot of different virtual manipulatives that can be used to really simplify different concepts…I’m stuck to a projector.”

Not having access to technological resources such as computers also makes it difficult for students to practice for computerized testing, which is how many of the state’s standardized tests and college entrance tests are administered. In Richmond City, one teacher explained. “[For] exceptional ed[ucation] students…we only have a few carts [of computers]…So, it was really hard trying to get computers for those students. And, so, it makes it difficult for them to practice…computerized testing.” She later adds, “They need that practice, because they need to practice the test the way it’s going to be presented.”

The insufficient availability of technological resources in the classroom has also forced some teachers to pick up the slack and ask for additional help. One Richmond City teacher explained that some of her peers, “are going through GoFundMe or Donate to My Classroom to get these things that are not being serviced for us.”

In the School: Student support staff and services are lacking

Support Staff Positions Play an Important Role

In addition to teachers and instructional staff in the classroom, support staff play many vital roles in Virginia public schools. These professionals care for the physical and mental health of students, help maximize student success, get students to and from school safely, and ensure that their schools are safe and clean. Yet, since the recession, many schools have cut back on these positions reducing services provided to students and pushing more responsibilities onto teachers.

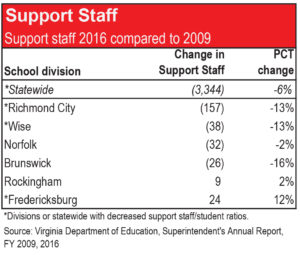

Public schools across Virginia employ 3,344 fewer support staff since 2009. That total includes support staff reductions in Richmond City (157 positions) and Wise (38 positions). These divisions now have fewer support staff relative to student enrollment, meaning schools are being stretched thinner in providing essential services. Fredericksburg has added support staff, but they have not been able to keep pace with growing student enrollment — similar as with teachers. Rockingham is a bit of an outlier going against the statewide trend in that they’ve actually increased support staffing overall since 2009, although they have made reductions for student health support positions.

Nursing Staff

School nurses are often the only staff in schools trained to make sure students get comprehensive medical care. Yet, some schools are now forced to share nurses — meaning students may not have access to a nurse on a daily basis, which in addition to jeopardizing their health could also impact their learning. The state has no requirements for schools to employ nurses or have manageable caseloads. This raises important concerns about the health and safety of Virginia students.

Other states, such as neighboring North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia, as well as Pennsylvania, have all defined student-to-nurse ratios to try and manage caseloads.

Richmond City and Rockingham have reduced their number of health staff — which includes school nurses, psychologists, and social workers — since 2009. Brunswick has brought on an additional staff member since 2009, yet the division only has four health staff for over 1,700 students. This ratio is below what is typical in the state, in which Brunswick would have five to six health staff.

The increasing number of students that school nurses serve has stretched each of these divisions beyond capacity. A teacher in Rockingham explained, “Our school is over capacity, and our nurse will see anywhere from 50 to 75 kids a day…There are days when she doesn’t get a lunch [break]. If she’s lucky, she’ll get a bathroom break.”

In Brunswick, educators explained that school nurses are shared across buildings and may not be available onsite. One Brunswick County teacher said that they have to rely on their career and technical education instructor, who happens to be a registered nurse, to provide health services for students. “We have a nurse, but she is only here [on] certain days,” she explained. “We also have a teacher who teaches the nursing students in the health occupations and CNA class. She gets called out a lot for things…Her students are suffering from that because she is having to be called out of her class from teaching.”

Counseling Staff

School counselors help address students’ academic, career, and developmental needs. They play a critical part in helping students achieve success. However, due to the limited number of counselors available in some divisions and their growing list of duties, many counselors spend a considerable portion of their time doing more administrative tasks, such as assisting with testing and class scheduling.

This is the case in Fredericksburg where one teacher explained that in her 12 years of teaching, she has seen declines in the time counselors have available to work with and develop students. She attributes this to the counselors’ larger role in assisting with preparation for SOL test administration. She says, “I know that our counselors work very hard, but they have so many other responsibilities, that to get into the classroom is very difficult.”

One Wise County administrator explained that one of their schools lost their guidance clerk. As a result, the school counselor has to do more administrative work, which takes away from her time to work with students. “Every piece of filing she has to do…, every SOL label she has to affix to a folder, all of that takes away from working with kids,” he said. “So, instead of spending 30 minutes working with a young man on some issue…she might hurry it up to 15 minutes because she has to fax over the record for the next student.”

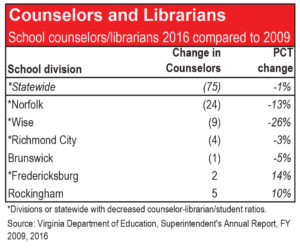

In addition to increasing responsibilities, many schools have also reduced the number of counselors they have to carry out those tasks. Norfolk, Richmond City, and Wise have all cut back on school counselors resulting in increasing caseloads for counselors and making one-on-one time with students more difficult. Fredericksburg has increased their number of school counselors, yet has not kept pace with growing student enrollment.

Custodial Staff

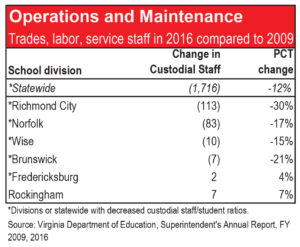

Many school divisions have looked to maintenance and operations for savings to help balance budgets while experiencing state cuts. Statewide, since 2005, school divisions spend about 8 percent less per student. Reducing custodial staff is one of the ways schools have found those savings. Schools employ over 1,700 fewer operations and maintenance staff since 2009. Richmond City by itself has eliminated 113 of these positions equal to a 30 percent decrease. Norfolk, Wise, and Brunswick have also made large reductions in staffing and Fredericksburg has not kept pace with enrollment growth.

These cuts have stretched custodial staff thin in order to maintain clean facilities for students and teachers. For example, in Norfolk, a teacher explained that his school does not have substitute custodial staff, which leaves their head custodian to pick up the loose ends when others are unable to report for work. “They don’t even have subs,” he said. “So if someone calls in, our custodial supervisor [has to come in]. [Last week], he had to work from 6:00[a.m.]-2:00[p.m.], and leave and comeback at 4:00[p.m.] and close the school down…[He] worked everyday last week from sun up to sundown.”

In Richmond, one teacher observed that their custodial staff has “tremendously decreased” for the last two years. “Our custodial staff are fewer, and they are being asked to clean more…because we don’t have enough…Some of our elementary schools only have two people, one who comes in the morning and stays until the afternoon. And, one that comes just before they leave and is suppose to finish up their work at some point during the night.”

Transportation Staff

Transportation staffing is another critical area school staff identify as a challenge. Most divisions — except for Fredericksburg and Richmond City — actually maintained or increased their transportation staff relative to student enrollment. Yet, schools have found savings in other ways, like not replacing school buses as frequently.

In Wise County, educators spoke about potential safety concerns with the age of their buses and the number of students per route. One educator explained that they have several buses that are 15 or more years old. State lawmakers encouraged schools to use aging buses when they increased the assumed lifespan for buses in the state budget up to 15 years without evidence that this is a safe assumption. A 2016 report notes that at least 1,900 buses statewide are near or past the recommended 12 to 15 year replacement cycle.

Teachers and administrators also identified challenges recruiting bus drivers, which has resulted in instances of overcrowding on buses for certain routes. A teacher from Wise, who is also a bus driver, said “I went from having roughly 30 something kids [to] 40 something kids [on my route]…in the past year, to this past week I had 68 students [on a bus].” Multiple other teachers chimed in after this comment, saying: “that’s not safe.”

To help deal with the shortage of bus drivers in Richmond City, one teacher has taken to recruiting parents of students to get their CDL license and become bus drivers. “With the bus driver situation, that has been ongoing for at least five or more years,” she explained. “And just from my own experience at my school…I was able to work with [a parent and] help her study. She got her CDL license and now she is one of our bus drivers. I am trying to get more on board!”

Changing student needs: English learners and economically disadvantaged students

English Learners

Student demographics are quickly changing across Virginia and so are the needs of students in the classroom. In particular, the number of English learners (EL) in Virginia public schools is growing rapidly — increasing by over 54,000 students since 2009. In Richmond City, the number of EL students has almost tripled since 2009 increasing by almost 1,500 students. Norfolk and Fredericksburg have had similar growth with enrollment more than doubling. In Rockingham, where recent growth hasn’t been as rapid, more than one in 10 of their student are EL.

All four of these divisions identified challenges providing needed staffing and instructional resources for EL students. In particular, schools did not have sufficient English language specialists and expressed difficulty both funding and recruiting these positions.

In Richmond City, the increase of EL students has been concentrated in schools on the southside of the city — where the number of EL students has grown to more than 2,000 from a little over 500 in 2009. One teacher there explained, “Our school division has had a problem with handling the abundant growth of our [EL] population, particularly on the Southside because that’s where it has grown the fastest. The problem is we don’t have enough translators in the building.”

This was also identified as a challenge in Norfolk. “I have an [EL] student in my class, and…we are trying to learn together,” explained one teacher. “I have an [English language specialists] that comes by one day a week for one hour [to work with her] — And this little girl knows very little English and her mother knows none, so I don’t have any resources for her other than for me to go to the computer, [which is] outdated, to figure out what to do with [her]…You can tell that she is a bright little girl, but we’re not giving her everything that she needs.

These EL students are being placed in general education classes with limited assistance from language specialists. This puts both the teacher and students in difficult positions as they try to communicate across language barriers. As a result, EL students are not getting the instruction that they need to be successful in the classroom and are struggling to perform on standardized tests. There is a sizeable gap between EL students and other students on SOL pass rates. For example, statewide only 63 percent of EL students passed their 3rd grade reading SOL compared to 77 percent of non-EL students. The gap is similarly large for math tests. Only 66 percent of EL students passed their Algebra 1 SOL compared to 84 percent for non-EL students.

Economically Disadvantaged Students

Virginia has over 488,000 economically disadvantaged students — eligible for free or reduced lunch or other public benefits — in its public schools. That’s almost four out of every 10 students. The number of economically disadvantaged students has been increasing dramatically — up 89,000 (22 percent) since 2009.

These students face serious challenges that can make success in the classroom more difficult. They are more likely to have distractions in their home life, such as moving frequently, hunger, and parents coping with substance abuse. Many do not have the luxury of outside resources that students from higher-income families may receive. They are less likely to be involved in organized activities like music lessons, clubs, or sports teams that can lead to social and mental development. The lack of resources and support puts these students on an uneven playing field when they enter the classroom.

In Norfolk, the schools have had to eliminate clubs and shorten after school programs which can be very beneficial for low-income students who are less likely to be involved in organized activities outside of school. One teacher explains “there [were] multiple programs for the children to be involved in to bring about a higher level of learning. That’s all gone.” The teacher observed that Norfolk has also eliminated financial incentives or stipends for teachers to work in inner city schools understanding that these positions incur additional costs.

Administrators and teachers in Brunswick, Norfolk, and Richmond City expressed concern that staffing reductions have impeded their ability to meet the needs of these students. In particular, reductions in school counselors — along with their increasing job responsibilities — have limited their availability for one-on-one counseling to assist students with challenges they may be experiencing outside of school. The elimination of reading and math specialists that provide remedial services also reduce one-on-one instruction which can be pivotal for students that might enter school with less preparation.

The impacts can be seen on test scores. The gap between economically disadvantaged students and other students on SOL exams has continued or worsened since 2009. The percentage of economically disadvantaged students passing their 3rd grade math exam fell from 81 to 65 percent and for 3rd grade English it fell from 77 to 62 percent. This decrease is much more severe than that experienced by students whose families are financially secure — where pass rates fell only a few percentage points and are now at 86 percent for math and 85 percent for reading. This is a disturbing trend where rather than closing the achievement gap, it’s actually growing.

Facilities Needs: Leaks, mold, and lagging upkeep

All Virginia students deserve a safe, clean, healthy school environment. However, in the face of shrinking state support, some school divisions struggle to maintain their facilities or pay for repairs. More than 70 percent of Virginia school divisions now spend less per student to operate and maintain facilities than they did 10 years ago with some spending up to 40 percent less per student. Overall, Virginia school divisions spent 8 percent less per student on operations and maintenance.

These cuts have also had very real impacts on the day-to-day activities of teachers and students. School administrators and teachers in Brunswick, Norfolk City, Richmond City, Rockingham, and Wise identified challenges maintaining their facilities.

In the cities of Richmond and Norfolk, teachers described how they prepare their classrooms and buildings when there’s a forecast of rain. One Richmond teacher said, “When I left on Friday, I left a trash can sitting on my desk in my office and a trash can on the back wall where the computers are.” Because, as she explained it, “When it rains, it leaks!” Similarly, in Norfolk, teachers explained that when it rains they have to place buckets “up and down the hallway…In our annex…most of [our tiles] are a brownish color and they are sinking and falling…And you can see water come down the walls, literally you can see the water.”

Mold is of such concern in one Norfolk high school, “That teachers are now writing to [the Occupational Safety and Health Administration]…That is how bad the mold is in that building,” explained one Norfolk administrator.

An administrator in Norfolk expressed concern about the general cleanliness and upkeep of school buildings, “You want the kids to go into a nice, clean environment. It’s hard to do that when you don’t have enough staff to…just literally clean …and do those things that keep the building up.” He said that custodial staff are forced to “hit the high spots” rather than doing a thorough cleaning of the facilities. Lack of upkeep has led to infestations of insects and rodents in some of the schools, including a problem with cockroaches in one of the cafeterias.

“We are constantly asked to do more, but with less,” explained one Richmond teacher. “And I don’t know if the people, if the powers that be…really know what it’s like for us…I think they need to go to all of [the schools] so that they can see the environment that our children and us are in on a daily basis…It is not an environment that they would want to work in nor send their children…I guarantee that!”

Path Forward

The experiences of teachers and school administrators across the state show that many schools are being pushed to the limit. Lawmakers need to take these resource challenges seriously and respond with substantive action to restore much needed support for public education. A good start would be for lawmakers to use the blueprint recently handed to them by Virginia’s Board of Education.

In November 2016, the Board unanimously approved common-sense amendments to improve support for Virginia public schools that they sent to lawmakers. The amendments would undo some of the harmful cuts made during the recession and ensure Virginia schools have adequate staffing for critical positions such as principals, assistant principals, school counselors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and other support staff. Many of these staffing positions are the very support positions that teachers and school administrators point to as being insufficient to support students and run schools smoothly.

Every student in Virginia deserves a fair shot at success in the classroom and after they graduate. Virginia’s economy demands a future workforce that is prepared with the skills, knowledge, and competencies to help make it thrive. These experiences from instructors around the state show that years of the state cutting corners to balance the budget has finally caught up with teachers and schools trying to do more with less. It’s time lawmakers adequately support Virginia schools and commit to investing in our future.

Methodology

The information is this report was collected through a series of eight focus groups with fifty participants that included teachers, teachers aides, principals, and other instructional staff. The focus groups were held in Brunswick County, Fredericksburg City, Norfolk City, Richmond City, Rockingham County, and Wise County. These localities were chosen to represent varied areas of the state based on geography and population density, and to identify localities with high percentages of students eligible for free or reduced lunch. A qualitative, semi-structured focus group approach was used for data collection. Participation was voluntary and responses were left anonymous. Each focus group was recorded to allow for the collection of direct quotes and responses from each participant.