September 26, 2018

Federal Responsibility, Local Costs: Immigration Enforcement in Virginia

Immigration enforcement is a federal responsibility, yet local communities across Virginia are paying for some of the costs through their local law enforcement’s voluntary cooperation with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Housing detainees, establishing local ICE programs, and maneuvering the related legal issues all increase costs for local governments — costs that are not reimbursed by the federal government.

| Detainers, IGSAs, and 287(g) agreements

Detainers: ICE can issue a notification or a detainer request after a person is taken into state or local custody. The notification request asks that the facility notify ICE when that individual is about to be released from the facility. A detainer requests that the local agency hold the person for an additional 48 hours (excluding weekends and holidays) after their scheduled release, giving immigration officers additional time to take them into ICE custody. Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs) and Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) care provider contracts: IGSAs are contracts between the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) or ICE and state/local governments to detain individuals who the federal government is holding on criminal or immigration matters for a negotiated amount of money. (USMS IGSA contracts can be used by all federal law enforcement agencies, including ICE.) In Virginia, about seven adult facilities (including the privately-run Immigration Centers of America facility in Farmville) have IGSA contracts with USMS or ICE. There are also two high security youth jails in Virginia with ORR contracts to hold immigrant youth, despite that ORR is required by law to house children in the “least restrictive setting appropriate for the child’s needs.” One of those ORR contracts will soon expire and is not being renewed, yet it appears that same youth prison occasionally holds children through an IGSA with ICE or USMS. |

In 2017, a federal Executive Order expanded ICE’s priorities for the interior of the United States. Since then, ICE has issued 80 percent more immigration detainers to local jails, and partnerships between ICE and local police departments have more than doubled. This growth would be impossible without manpower from local law enforcement agencies and funds from state and local governments, which strains local budgets and resources. Voluntary cooperation with ICE also opens local governments to legal liability in cases where ICE requests may violate constitutional protections or jail crowding results in unsafe conditions for inmates.

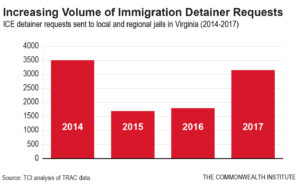

ICE sent over 3,100 detainer requests to local and regional jails in Virginia during fiscal year 2017. This is a 75 percent increase from the prior year. If these jails had accommodated the requests, the cost would have been almost $830,000. And using local resources to facilitate federal immigration law enforcement risks increasing economic and social harms to Virginia families and communities.

This report examines how Virginia localities facilitate federal immigration efforts and what implications these relationships have on local resources.

Immigrants in Virginia

In 2016, Virginia was home to more than 1 million foreign-born residents, making it the ninth largest immigrant population in the country. And Virginia’s immigrants come from a wide range of countries, including 10.3 percent from El Salvador, 8.7 percent from India, and roughly 5 percent each from the Philippines, Mexico, and Korea. Immigrants in Virginia are well educated and active in the economy — over 40 percent hold bachelor’s degrees or higher and immigrants represent almost 20 percent of Virginia business owners. Virginia immigrant household median incomes are higher than national averages as well.

Immigrants account for 12 percent of Virginia’s population, holding a wide range of immigrant statuses including naturalized citizens, temporary visa holders, and unauthorized immigrants. A number of Virginia’s immigrants live here under Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), both of which authorize immigrants in special circumstances to lawfully live in the United States. However, many people who currently have TPS or DACA status will soon be considered undocumented unless federal action is taken to extend these programs, leaving them in danger of being deported to an unsafe or unfamiliar country.

TPS authorizes foreign nationals to live in the United States if their home country is experiencing conflict or a natural disaster. In Virginia, there are 23,500 TPS holders from El Salvador and Honduras who will become undocumented immigrants when their status is terminated in 2019 or 2020 due to the U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security’s decision to not renew protected status for people from these countries. These individuals have lived and worked in the United States for decades, contributing to communities and raising families with a combined 21,200 children. By changing their status to undocumented, they can be deported if accused of a minor crime, and the significant negative social impacts of immigration enforcement will be amplified.

Meanwhile, DACA was established in 2012 for undocumented children who arrive in the United States before the age of 16, allowing them to defer deportation and get a work permit if they meet certain education requirements and do not have a criminal record. In 2017 the Trump Administration announced it would repeal DACA. However, a U.S. District Court ordered DHS to continue allowing recipients to renew their status. The federal government has put new DACA applications on hold, although this decision is under court challenge as of the publication of this report. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that, should new DACA applications be accepted, nearly 20,000 Virginians would be eligible to apply. Unless or until that happens, these young Virginians who arrived in the United States as children are considered undocumented immigrants and are at risk of being deported to their birth countries, even if they do not speak the native language and are unfamiliar with the region. And other litigation to end the DACA program altogether puts the 10,200 Virginians who are current DACA recipients at risk of deportation.

Immigrants account for a large number of Virginians and are a vital part of Virginia communities. Carefully examining policies that affect immigrants will ensure that Virginia is a safe place for every resident, while minimizing the negative social impacts that immigration enforcement has on immigrant families.

ICE Detention in Virginia

If the U.S. Department of Homeland Security suspects a person is unlawfully living in the United States, ICE can issue a notification or a detainer request after the person is taken into state or local custody.

The notification request asks that the facility notify ICE when that individual is about to be released from the facility. A detainer requests that the local agency hold the person for an additional 48 hours after their scheduled release, giving immigration officers additional time to take them into ICE custody. However, local agencies are not obligated to hold people for an additional 48 hours and doing so without a valid court order has been found by 12 state and federal courts to be unlawful or in violation of constitutional rights.

As of 2017, ICE detainers are accompanied by an “administrative warrant.” However, this still does not make compliance mandatory because this warrant is not approved by a judge. Moreover, ICE can take an individual into custody before they have been tried or convicted of the criminal charge that may have prompted the filing of the detainer, leaving the state or local criminal justice systems with an unresolved case and an individual, who has not been convicted of a crime, facing deportation.

From October 2016 through September 2017, the most recent completed federal fiscal year, ICE issued detainers requesting that facilities in Virginia hold almost 3,500 people for an additional 48 hours because ICE suspected that the individual was an undocumented immigrant (ICE issued just 92 notification requests to Virginia facilities over the same time period). Most of those detainer requests — over 3,100 — were sent to local and regional jails. Facilities complied with at least 70 percent of the detainer requests and just 1.4 percent of detainer requests are recorded as being refused by facilities (their responses to 25 percent of the requests are unknown).

To the extent that these detainers resulted in Virginia’s local and regional jails holding individuals past the day they would otherwise be released, complying with this high volume of ICE detainer requests creates significant costs for local governments, while risking additional lawsuits against localities.

After a slowdown in detainer requests in the final years of the Obama administration, there has been an increase in these requests in fiscal year 2017. In FY 2014, over 3,500 detainer requests were sent to local and regional facilities in Virginia. However, this number fell to about 1,700 requests during FY 2015 before slightly increasing to 1,800 during the following fiscal year. By FY 2017, detainer requests rose to over 3,100, near their previous level. A majority of these were sent to just seven local and regional jails out of over 80 local, regional, state, federal, and ICE facilities located in Virginia. These seven facilities complied with a total of 1,627 detainer requests:

- Prince William – Manassas Regional Adult Detention Center

- Fairfax County Adult Detention Center

- Arlington County Jail

- Loudoun County Jail

- Alexandria City Jail

- Rappahannock Regional Jail

- Chesterfield County Jail

In addition to holding individuals on immigration detainer requests, a number of Virginia jails and two juvenile detention centers hold federally-responsible detainees, including immigrants, through intergovernmental service agreements (IGSAs) or, in the case of immigrant children, an ORR contract. Unlike detainer requests, IGSAs contain provisions for the federal government to pay the localities a per-diem rate for holding the immigrant detainees. However, holding additional people in local jails can still present fiscal challenges to local governments, including direct costs if the negotiated per-diem rate does not cover all costs and an increased risk of lawsuits. For example, the Rockingham-Harrisonburg Regional Jail had an average operating cost of $88.58 per inmate, per night during FY 2016, yet the jail’s federal per diem income was just $72.12. Recognizing these drawbacks, in May 2018 the Fairfax County Sheriff’s Office terminated their service agreement with ICE and, at the same time, announced that the office will not hold individuals on detainer requests unless there is a corresponding lawfully issued criminal detainer. Similarly, the Northern Virginia Juvenile Detention Center — one of only a handful of high-security youth jails in the country that are known to be holding children for ICE or ORR — announced in June 2018 that it will be ending its contract with ORR.

Cost of Complying with Detainer Requests in Virginia

Facilities in Virginia receive the eighth most detainer requests in the country — nearly 3,500 requests were made to federal, state, and local facilities during FY 2017. This is a substantial amount of federal requests made to Virginia localities, each of which is solely responsible — financially and legally — for holding individuals in their facilities, where it costs an average of $85.17 per inmate each day.

Of the nearly 3,500 requests made to all facilities during FY 2017, ICE sent over 3,100 requests to local and regional jails in Virginia. If these jails had accommodated the requests by holding every individual for an additional two days, the cost would have been just under $830,000 using the per capita, per day operating costs for jails that received detainer requests. It is important to note that this figure is likely an underestimate of the total cost. Meanwhile some jails hold immigrants for longer than the 48 hour period when complying with ICE detainers, particularly whenthe 48 hours includes weekends and holidays.

Funding and Cost Sharing Immigrant Detainment in Virginia Jails

The cost to operate local and regional jails falls heavily on local governments. The federal government provides very little financial support for local and regional jails in Virginia, aside from per-diem reimbursements for holding federally-responsible detainees (these per-diems are not provided for complying with ICE detainer requests). And the state, which covered 46 percent of total costs for Virginia jails prior to the cuts of the Great Recession, now pays just 41 percent of the costs. Localities are left paying nearly half the total bill. Overall, regional and local jails in Virginia spent $875.9 million on operating costs in FY 2016, with local governments covering $474.7 million of that cost.

In Virginia, the majority of ICE detainers are being sent to jails where complying with detainers is more expensive than anywhere else in the state. Most of the jails that receive high volumes of detainer requests are located in Northern Virginia, where the general high cost of living means the cost to house inmates is very high. Moreover, nearly 70 percent of jail costs in the northern region of the state are locally funded, which means local taxpayers burden most of the cost of detaining immigrants on ICE’s behalf.

287(g) Agreements In Virginia

Immigration detainers are not the only method by which ICE responsibilities — and their costs — are delegated to states and localities. In 1996, Section 287(g) was added to the Immigration and Nationality Act, permitting the federal government to deputize selected state and local officers as ICE officers capable of performing immigration enforcement functions. Under this program, known as 287(g), DHS enters into written agreements with non-federal law enforcement agencies and provides training to designated officers of the partnering state or local agency.

By assuming ICE authority and responsibilities, local law enforcement agencies can adopt a “jail enforcement” model where officers trained by ICE identify and process undocumented individuals who have already been arrested for an unrelated criminal charge. Another model — the “task force” model — permits officers to perform ICE duties during patrols or investigations, therefore enabling them to identify and process undocumented immigrants in the community. Alternatively, agencies can also choose to participate in a hybrid version of the models. However, no active 287(g) programs currently operate under a task force or hybrid model.

ICE has 78 of these agreements with local law enforcement agencies across the country. But ICE is not responsible for the cost of implementing these agreements, and it falls almost entirely on the backs of local agencies, putting a strain on local resources. Although ICE is responsible for operating the four-week training program for new 287(g) program officers, local law enforcement agencies are responsible for all of their personnel expenses. These expenses include transportation to the training program, salaries, overtime, benefits, and more. Upgrading a local agency’s infrastructure to accommodate new immigration enforcement technology also gets billed to the local agency, not ICE. The local agency is even required to provide administrative supplies and free office space to ICE personnel at their request.

Multiple counties in Virginia adopted 287(g) agreements in the late 2000s, however only two 287(g) agreements exist in the state as of July 2018: Prince William – Manassas Regional Adult Detention Center’s 2007 agreement and Culpeper County’s agreement signed this spring. Until 2012, Prince William County Police Department also participated in a 287(g) program, which gained attention for its staggering projected costs.

Prince William County

After rapid growth in Prince William County’s Hispanic population during the early 2000s, the County Board and police department elected to participate in a 287(g) agreement, under the task force model. Initial cost projections for implementing the agreement were $26 million over the next five years, alongside a nearly $800,000 withdrawal from the county’s contingency fund and revenue from a property tax increase. However, modifications to the agreement eventually cut cost projections down to $11.3 million over a five-year period.

The program had additional deleterious effects on the community, including a significant decline in Hispanic population growth and a decline in public trust of the police. In 2012, ICE announced the end of all task force model 287(g) programs, including Prince William County’s. However, Prince William – Manassas Regional Adult Detention Center’s jail enforcement 287(g) program has remained intact.

Culpeper County

In spring 2018, the Culpeper County Sheriff’s Office signed a 287(g) agreement with a jail enforcement model that will place new demands on local resources.

While Culpeper County Sheriff Scott Jenkins issued a statement saying that he has not requested additional funds for his budget, it is likely that deputizing jail employees to carry out immigration enforcement will result in heavier demands on staff and other resources. This strain will eventually cost the county more money in the form of additional overtime, additional staff turnover, and potential full-time equivalent staff. And ICE will not pay for these costs — ICE is only responsible for their own personnel and for providing training material.

Legal Liability

When state and local law enforcement comply with detainers and enforce immigration policies, they shoulder the majority of the cost. These costs can be especially burdensome because they often extend beyond duties in partnership with ICE and take shape as expensive legal disputes. In instances where immigrant rights are violated by local law enforcement performing ICE duties, individuals and advocacy groups across the country challenge localities in state and federal court.

In 2014, an Oregon woman named Maria Miranda-Olivares was arrested and then blocked from posting bail because of an ICE detainer. She spent two weeks in jail awaiting adjudication for her unrelated criminal case, then an additional 19 hours in jail because of the ICE detainer. Miranda-Olivares sued Clackamas County, Oregon and the Oregon Federal District Court ruled in her favor, that an ICE detainer was not sufficient for holding an individual in jail. This ruling cited a previous case, Arizona et. al. v. United States, where the Supreme Court stated that detaining an individual only to investigate their citizenship may infringe on their constitutional rights. Because ICE requests do not come with a court order or warrant, compliance with them is a warrantless arrest.

Miranda-Olivares v. Clackamas County and other cases have paved the way for successful litigation against localities that enforce federal immigration laws. In Maricopa County, Arizona, the police department’s unconstitutional and unlawful immigration enforcement practices amassed an estimated $150 million in legal and court-ordered monitoring fees. The county even had to raise property taxes to pay for court-ordered reforms. Although these costs were incurred while carrying out ICE policies, the federal government does not reimburse for them. So any locality that complies with detainers or hosts a 287(g) program makes itself vulnerable to the liabilities associated with these decisions.

There have been several similar immigration lawsuits in Virginia. In 2015, an immigrant sued Henrico County and its sheriff when the jail complied with an ICE detainer request, unlawfully detaining the individual more than 48 hours. Henrico County spent nearly $23,000 on the lawsuit: $12,000 to settle the case and $11,000 for legal expenses. It is likely that this will not be the last lawsuit of its kind, as state and federal courts across the country have deemed ICE detainers unconstitutional under the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment.

Another high-profile Virginia immigration lawsuit involves the Shenandoah Valley Juvenile Center (SVJC) in Staunton. The Center is the defendant in a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of immigrant children at the facility. SVJC is a secure facility for non-immigrant Virginia youth who are being held on state or local charges, while also detaining approximately 30 immigrant children who, according to the lawsuit, have been subjected to racial discrimination, excessive force, and extreme discipline. While the Center receives an annual grant from the federal government to defray the cost of detaining immigrant children, it is being sued for violating the children’s rights under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. Court proceedings for the case will continue through the fall of 2018.

Fortunately, some Virginia localities concerned with the constitutionality of ICE detainers have established limits on how long they will hold individuals without a court order. For example, the Fairfax and Chesterfield County sheriffs’ offices have a policy requiring a legal court order before complying with an ICE detainer request, per the advice of the County Attorney and the Virginia Attorney General.

Impact on the Economy and Communities

In addition to the direct fiscal costs, when local sheriff’s offices and police departments choose to use their resources to assist ICE, there can be harmful impacts for local families and communities. When Virginia residents are held in jail on a detainer request past the date they would otherwise be released, they cannot work, see their families, or take care of their children. And when local law enforcement is seen as acting as an arm of ICE, community members become less willing to cooperate with the police, making it harder for police to investigate criminal offenses.

This has consequences for families and communities across Virginia, and children are often the most vulnerable. If a parent is deported, children have worse outcomes in almost all aspects of their lives and are less able to be productive contributors to the economy as adults. Median income for immigrant households on average drops from $36,000 to $15,400 when a family member is deported. This is well below the poverty line for a family of three ($20,780 in 2018) – adding to a host of additional challenges for children growing up in these families. And should the primary caregiver be deported and the child enter foster care, the public is hit with a secondary cost of caring for these children if they end up in the foster system at around $26,000 per year.

In addition to the direct fiscal costs, when local sheriff’s offices and police departments choose to use their resources to assist ICE, there can be harmful impacts for local families and communities.

Nearly one in four children in Virginia live in households with at least one immigrant parent, and even the threat of deportation from increasing immigration enforcement and rhetoric about enforcement can have harmful consequences for these children.

The vast majority of these children are U.S. citizens (at least 86 percent) and the majority of the parents are lawfully present. Yet children in immigrant families have recently experienced an increase in trauma-induced symptoms that stem from anti-immigrant rhetoric, regardless of a parent’s immigration status. That’s because kids in immigrant families often cannot tell the difference between the rhetoric they hear and whether threats of deportation apply to their family.

Conclusion

Using local resources to enforce federal immigration law through complying with immigration detainer requests and implementing programs like 287(g) generates demands on local resources that go unreimbursed by the federal government. As ICE’s expanded immigration priorities become reflected in Virginia, local communities will face significant additional fiscal costs as well as social costs. Enforcing federal immigration laws has proven to be an expensive responsibility for localities, especially because these laws are often open to interpretation — or misinterpretation. Virginia localities can and should decline to use local resources to voluntarily participate in federal immigration enforcement activity.

Read the Release (pdf)