May 21, 2019

Standing at the Crossroads: Virginia has an Opportunity to Invest in an Equitable Future

Virginia is a wealthy state with the resources to invest in creating broadly shared opportunity and prosperity. How we choose to invest our shared resources through the state budget shapes the commonwealth’s future and can fortify the building blocks of opportunity, such as education and public health.

The current moment in Virginia provides an opportunity for reflection on our funding priorities and planning for the future. During the 2019 legislative session, policymakers recognized the 400th anniversary of the first meeting of the representative legislative assembly in Virginia, the importation of the first enslaved Africans into Virginia, and the recruitment of large numbers of English women to move to Virginia to act as wives for English colonists. This history invites further consideration of the ways public policy has and can be used to create or dismantle opportunity.

Legislators make choices each year on policy that will shape the commonwealth. For 400 years, public policy has too often been used to erect barriers for communities of color, with the frequent effect of also harming low-income white communities. At the same time, however, Virginians have worked to turn public policy into a tool that can improve the lives of every Virginian. And this work has made a difference.

An important way to continue this work is through the state budget — one of the most important policy documents that is considered by legislators each year.

An important way to continue this work is through the state budget — one of the most important policy documents that is considered by legislators each year. State budgets can advance the adequacy and equity of our investments or further entrench barriers to opportunity for every community, particularly for communities of color. Every new investment, funding cut, and change in policy language represents a decision about what and who Virginia values.

Good schools, access to affordable health care, and economic opportunity so that every child can reach their full potential are core responsibilities of our state government.

Strong, well-supported schools are vital to making sure that every child in every neighborhood is able to pursue their educational and career ambitions. They are also vital to the health of the local economy which depends on having talented, well-educated workers. Now is the time for Virginia to take the lead and make high-quality education our calling card. We can do this by eliminating recession-era gimmicks such as the state’s cap on support staff and by improving the equity of our funding structure to ensure that each student has the resources and opportunities to be successful. With adequate investments through the state budget, we can make educational opportunity a reality that lifts every individual student to new heights and, with them, the communities they live in.

Like a high-quality education, access to affordable health care is critical for people of every age, occupation, and health status across the state. Lack of health coverage is often a major barrier to addressing health concerns before they turn into serious, long-term ailments. We all want to live with the confidence that an accident or unexpected illness will not lead to massive out-of-pocket costs and eventual medical bankruptcy. Weighing the prospect of major health care costs to other essentials like food, housing, and transportation expenses is something no family wants to face. For families with low incomes, this situation occurs far too often, leading to missed opportunities for medical intervention and preventative care.1 Making health coverage more comprehensive and affordable would help more individuals and families stay healthy and striving towards their goals. In particular, providing dental coverage for people who receive health care through Medicaid, removing extra hurdles facing lawfully present immigrants in accessing health insurance, and making sure every child has health insurance are important steps Virginia should take as soon as possible.

And we all want communities where every parent can find a job that pays enough to support their children with dignity. That is not true right now in Virginia, and that is because past public policy decisions have created pockets of disinvestment where too many families — particularly families of color — are unable to get good jobs and provide safe healthy housing for their children.

Today’s leaders have the opportunity to begin to dismantle some of those barriers and promote shared prosperity.

Today’s leaders have the opportunity to begin to dismantle some of those barriers and promote shared prosperity. We can pay state employees and employees of state contractors a living wage. We can invest in need-based financial aid for students at Virginia public colleges and universities. We can connect new residents with critical information to help navigate Virginia’s economy. And we can make sure working Virginians are fairly paid and law-abiding businesses get a fair chance by adequately funding Virginia’s wage enforcement unit.

Where We Stand

As a top-10 state when it comes to median household income,2 Virginia has the capacity to more adequately fund investments in our communities. Yet we are in the bottom 10 states when it comes to state investment in preK-12 education, per-student support for higher education, and Medicaid.3 We can do better.

There have been some steps forward. In 2018, Virginia policymakers came together and accepted federal funding to expand access to health coverage for low-income adults through Medicaid. Despite pending work reporting requirements that will likely see many Virginians lose coverage, Medicaid expansion is providing quality health care to over 270,000 Virginians,4 helping them get and stay healthy so they can fully participate in our communities and economy.

The state’s recent track record on available resources is more mixed. Although state revenues have increased in recent years, the state is still behind its position from a decade ago and less prepared for the next recession. In December 2018, the administration announced that the state had $1.6 billion in new General Fund (GF) revenues for the 2018-2020 budget cycle.5 These new resources could have made a big difference in helping to remedy low investment in key areas. However, state lawmakers and the administration chose to use about $800 million — about half — toward tax cuts and another $160 million was set aside with the intent of using it for future tax cuts.6 These decisions by state lawmakers reduce the impact that these new resources could have in our communities. Meanwhile, a new law will generate additional sales tax revenues from out-of-state internet purchases (effective July 2019), but these new GF revenues are expected to be much lower than initial estimates.7

We all want the best for Virginia, and we all have a stake in making sure that the state raises the resources it needs to fully meet the needs of our communities.

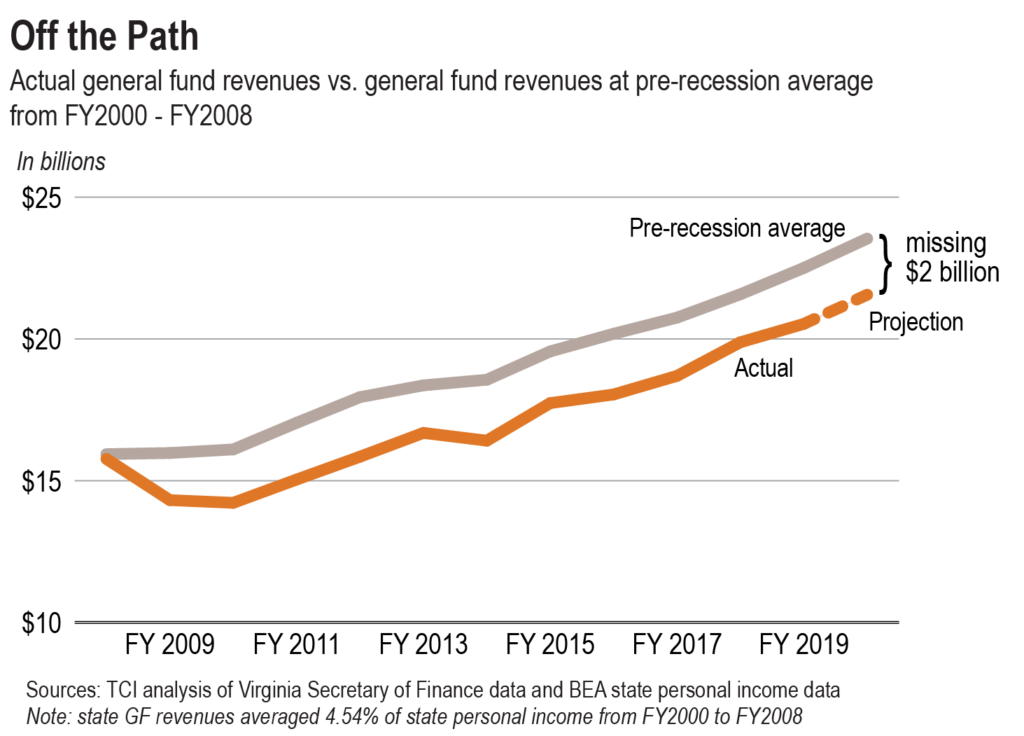

We all want the best for Virginia, and we all have a stake in making sure that the state raises the resources it needs to fully meet the needs of our communities. However, over the last decade state General Fund revenues have not kept up with growth in state personal income, leaving Virginia with fewer resources than could be available to invest in key priorities. Despite the ongoing economic expansion — with a state unemployment rate under 3 percent8 — and our status as a top-10 state when it comes to median income, Virginia’s state revenues are still off track from where the state was before the recession. From fiscal year 2000 to fiscal year (FY) 2008, state GF revenues represented on average 4.54 percent of state personal income.9 Since FY 2009, however, Virginia’s GF revenues as a share of state personal income have hovered around 4.07 percent. Even with higher state revenues in recent years, state GF revenues are projected to represent only 4.14 and 4.15 percent of state personal income for FY 2019 and FY 2020. If the state had maintained its pre-recession average, Virginia would have an additional approximately $2.0 billion per year – resources that could be used for investments in K-12 education, health care, and other public services. Over the past several years, state lawmakers have chosen to generate new non-GF revenues to fund specific priorities like transportation,10 but these new resources are not sufficient or flexible enough to make sure that Virginia can maintain and improve core public services.

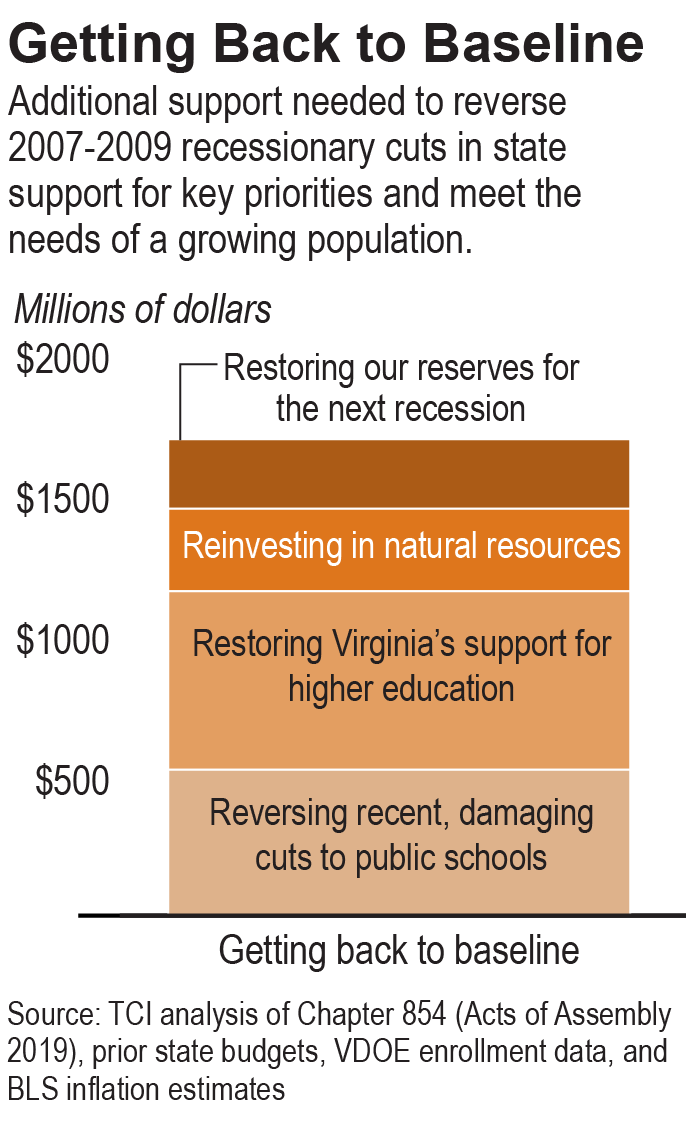

The impact of low state investment is perhaps most obvious in the area of education, where Virginia’s local communities and families have been forced to shoulder more of the burden. State K-12 funding is still down 8 percent per student, adjusting for inflation, since 2008-2009 when the Great Recession impacted the state’s resources.11 If the state spent the same per student as we did back then, the General Assembly would have appropriated an additional $580 million in direct aid to public schools across the commonwealth for the 2019-2020 school year.12 As a result, many schools have been forced to cut back. Staffing statewide is still down since 2008-2009, while enrollment has grown by more than 55,000 students.13

State higher education funding is also still down dramatically (16.5 percent per student) since 2008, adjusting for inflation,14 and the state is failing to meet its own policy for sharing costs with students and families. According to state policy, the state should be covering about two-thirds (67 percent) of the cost of education. Yet instead, the state covered less than half (45 percent) of costs in 2018-2019. The State Council of Higher Education for Virginia estimates that if the state share aligned with the policy goal, then tuition costs would be as much as $3,000 lower.15

And on top of still being behind where we were a decade ago for investing in critical public functions such as education, we are not well prepared for when hard times next hit. Saving for the next recession is important. The current economic expansion is already the second longest one on record, yet Virginia’s legislators have put the minimum required amount into the traditional rainy day fund,16 instead putting money into a new, more flexible reserve fund. Even when combining those funds, we are below where we should be. The balances in Virginia’s rainy day fund and revenue reserve are expected to total about $1.34 billion heading into the next two-year budget cycle.17 At its previous peak before the last recession, Virginia’s rainy day fund balance was $1.48 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.18

Funding a Better Future

Looking forward, state government can make transformative investments while also building up our reserves to adequate levels, but policymakers have to be willing to discuss revenues as part of that process. Due to recent federal and state tax changes, the state’s revenue picture is still coming into focus. Given the growing economy, the state budget should have additional resources available in coming years. But lawmakers still need to repair the state budget from cuts made during the last downturn and keep up with changing needs and priorities. To do so, state lawmakers need to consider policies that will provide a sustainable boost to the state’s resources.

Today, the wealthiest 1 percent of U.S. households own more than the bottom 90 percent,19 and the concentration of wealth closes off opportunity for low- and moderate-wealth families. Before July 2007, Virginia had its own estate tax. A state tax on inherited wealth is a powerful tool to build shared prosperity. Because of large exemptions that are built into estate tax laws, only the very wealthiest households would be subject to this tax. Reinstating it could generate nearly $70 million in additional state revenue per year, providing resources for more adequate investments and more opportunities in each of our communities.20

Virginia lawmakers also need to take a fresh look at the state’s income tax code. During the 2019 General Assembly session, Virginia lawmakers made some major changes to state income tax deductions, such as increasing the state standard deduction by 50 percent (from $3,000 to $4,500 for a single filer). However, the Virginia tax code’s overall rate and bracket structure — put in place in 1987 — remains unchanged. Virginia’s top rate of 5.75 percent begins at taxable income above $17,000. The current system does not reflect income changes that have occurred over the past several decades and the higher ability to pay among the highest-income households. Creating a new top rate for households with the highest incomes could generate additional resources for investments. One proposal to create new top rates for filers with incomes above $500,000 and above $1 million was estimated to generate between $255.8 million and $361.5 million each year over the first six years.21 Policymakers could use some of the revenue from these reforms to make Virginia’s overall tax code fairer by making the state Earned Income Tax Credit refundable and provide support to the state’s working families.

State lawmakers could also do more to modernize the state’s corporate income tax system. Today, many large, multi-state corporations can shift profits earned in Virginia to subsidiaries in other jurisdictions where tax rates are lower or businesses are not taxed at all. To counter this practice, 27 states and D.C. have passed “combined reporting” laws that require companies to add up all of the income from all entities and apportion it to the states where the money was made. By enacting combined reporting, Virginia would gain $165 million a year and also end a tax advantage that local businesses do not get.22 This change would make sure large corporations pay their fair share in taxes and allow the state to invest more in critical priorities.

Building a Virginia with Shared Prosperity

This boost in state resources can give legislators the footing they need to take steps towards practical solutions that will help every family thrive.

Strong schools

Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On directs funds to school divisions with high concentrations of poverty to provide students with programs and services like counseling, drop-out prevention, and college access programs. Increasing funding for this program can address inequity in our school funding, yet it pales in comparison to other states — providing 1-16 percent more per student eligible for free lunch compared to the 20-25 percent more provided by most states with this funding.3 The state should strengthen this program by funding it more in line with other states. Spending 1-25 percent more per eligible student would take an investment of about $64 million annually from the state.24

This change is needed because Virginia’s primary education funding program (the Standards of Quality) is largely driven by enrollment and does not sufficiently factor in student demographics. This is an antiquated approach to funding schools. Over the past couple decades, many states across the country have transitioned to a model called weighted student funding, where cost estimates are based on the students and their needs, rather than just enrollment or programs. States that have transitioned to weighted student funding include California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Oregon, North Dakota, South Carolina, and Rhode Island. In total, 24 states in the U.S. provide additional funding through their primary funding formula for students identified as at risk of not graduating due to economic disadvantage and other factors.25

High-quality, affordable colleges and universities

Adequate investments in need-based financial aid is vital, because in-state students in Virginia have seen a significant rise in tuition costs. The average tuition bill grew by nearly 55 percent between 2008 and 2018 after adjusting for inflation, while real median incomes for Virginia families only grew about 2.4 percent between 2008 and 2017. The problem is especially serious for Black, Latinx, and low-income students. In 2017, the average tuition and fees at a public four-year university accounted for 16 percent of the median household income for white Virginia families, and 12 percent for Asian families, both below the state average of 17 percent for all families. Meanwhile, it accounted for 25 percent of median household income for Black families and 19 percent for Latinx families.26 In the 2019 legislative session, the governor and legislature increased need-based financial aid by $15.5 million.27 This investment is a start that we need to continue to build upon, if we aspire to make higher education affordable for everyone in the commonwealth.

Access to health coverage

In Virginia, lawfully present immigrants with permanent residency must establish a 40-quarter (10 year) work history, concurrent with the federal five year requirement, before qualifying for Medicaid.28 Virginia is one of only six states to have such a requirement. Though work quarters of spouses and parents can be included in the calculation, single immigrant adults without parents in the United States would have to wait 10 years or more for health coverage. Older immigrants who arrive in the United States later in life may never be able to satisfy this requirement. (Pregnant women, children, and a few other categories of immigrants such as refugees, asylees, and veteran families are exempt from having to meet these onerous standards.)

If Virginia lawmakers act to remove this obstacle, the federal government would provide the majority of funding for Virginia to ensure access to health care for immigrants with permanent residency. Two companion budget amendments that were ultimately not adopted in the House and Senate during the 2019 legislative session estimate that implementing this rule change would bring in $16.6 million in federal funding to provide these services and cost the state $6.6 million.29 This state cost estimate does not include any savings that would likely occur from the state not having to reimburse expensive emergency room visits by immigrants who are ineligible for full Medicaid coverage and are currently uninsured.30

Thriving communities

There are a number of other ways state policymakers can invest in building a more inclusive and prosperous future.

For example, policymakers could choose to pay state employees and employees of state contractors — including health care workers paid through Medicaid — a living wage of at least $15 an hour. This would have a real cost — at least $176 million per year in general fund costs31 — yet it would also have real benefits for Virginia families and communities. Public employment has long been a key pathway into the middle class for immigrant communities and, at times, African American communities in the United States. Yet some public employees and workers of public contractors are not paid enough to make ends meet. And Black and Hispanic workers continue to be paid less than white workers in Virginia. The typical white worker made over $23 an hour in 2018, $1.32 more per hour than in 2007 after adjusting for inflation, while Black and Hispanic workers typically made only about $16 an hour, $0.10 and $0.23 less, respectively, than in 2007.32 This is an issue that particularly affects personal care attendants, many of whom are people of color.

Virginia funds its state wage and hour enforcement unit at a level below what is needed to protect workers. Without proper funding, the state does not have enough officers to properly investigate all wage claims. Latinx and African American workers are most often cheated by employers who do not pay their workers at least minimum wage. While 8 percent of white workers in a multi-city study were paid under the legal minimum wage, 19 percent of Black workers, 33 percent of Latinx workers, and 15 percent of Asian American or other workers were paid under the minimum wage. A modest investment of $515,231 would provide support for five additional compliance officers.33

Another low cost way for legislators to move toward building a better future for each Virginian is to create a state Office of Immigrant Assistance. Policy makers across the political spectrum in Ohio, Michigan, New York, Illinois, and Massachusetts have embraced and started statewide opportunity offices for new immigrants to connect new residents to job and training opportunities, reputable local nonprofits and legal services, and resources to become full citizens. For years, Virginia lawmakers have put forth proposals to start a state Office of Immigrant Assistance, but the General Assembly has consistently failed to pass the legislation. Virginia should consider making this relatively small investment (around $440,000 to start and $280,000 annually after the first year) that will yield big returns.34

Conclusion

While the official commemorations of the 400th anniversary in Virginia have focused on the uplifting themes of democracy, diversity, and opportunity, the reality of Virginia’s past has been far more complicated and troubling. Public policy can be used to create or block opportunity, and for too many years policymakers in Virginia have failed to invest in building opportunity and, instead, have often built barriers for many people, particularly people of color.

Smart fiscal policies at the state level, both in how we raise and how we invest our shared resources, will move us toward a Virginia with broad opportunity and prosperity for all of us, no exceptions.

At this crossroads in history, Virginia policymakers should choose to use their power to improve the lives of every Virginian by removing the hurdles that prevent too many people from reaching their full potential. Smart fiscal policies at the state level, both in how we raise and how we invest our shared resources, will move us toward a Virginia with broad opportunity and prosperity for all of us, no exceptions.

Endnotes

- Cunningham, P.,“Why Even Healthy Low-Income People Have Greater Health Risks Than Higher-Income People,” The Commonwealth Fund, Sep 2018

- TCI analysis of 2017 American Community Survey and 2018 Bureau of Economic Analysis data

- “Virginia Compared to Other States, 2019 Edition,” Virginia JLARC

- “Expansion Dashboard” as of 5/3/2019, Virginia DMAS

- “Economic Outlook and Revenue Forecast,” Virginia Secretary of Finance, Dec 2018

- Fiscal Impact Statement (FIS) for SB1372 (2019),Virginia Dept of Taxation, and Conference Report on the 2018-20 Budget (HB 1700) Feb 2019 presentation, House Appropriations Committee

- FIS for HB1722 (2019), Virginia Dept of Taxation, and Retail Sales and Use Data Requests from Virginia Secretary of Finance presentation to House Appropriations Committee, Oct 2017

- Local Area Unemployment Statistics for Mar 2019, Bureau of Labor Statistics

- TCI analysis of Secretary of Finance state revenue reports; Virginia’s state budget; and BEA data

- Okos, S.,“Destination Unknown,” TCI, Apr 2013, and Wodicka, C., “I-81 and Other Projects Get Funding Boost,” TCI, Apr 2019

- TCI analysis of Direct Aid Payment Calculations, Virginia Dept of Education, and BLS inflation data

- Ibid.

- TCI analysis of Superintendent’s Annual Reports Tables 17 & 18, Virginia Dept of Education

- “Unkept Promises: State Cuts to Higher Education Threaten Access and Equity,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct 2018

- “2018-19 Tuition & Fee Report,” Virginia Secretary of Finance, Dec 2018

- TCI analysis of Virginia APA reports

- TCI analysis of Virginia state budgets and “Economic Outlook and Revenue Forecast,” Virginia Secretary of Finance, Dec 2018

- “Economic Outlook and Revenue Forecast,” Virginia Secretary of Finance, Dec 2018

- “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Sep 2017

- FIS for SB390 (2018), Virginia Dept of Taxation

- Ibid.

- “A Simple Fix for a $17 Billion Loophole: How States Can Reclaim Revenue Lost to Tax Havens,” ITEP, Jan 2019

- Verstegen, D.,“How Do States Pay for Schools? An Update of a 50-State Survey of Finance Policies and Programs,” University of Nevada, Reno, Mar 2014

- TCI analysis of Virginia’s state budget (Ch 854, 2019) and VDOE free lunch division reports

- “The Importance of At-Risk Funding,” Education Commission of the States, Jun 2016

- TCI analysis of tuition/fee data from SCHEV and 2017 ACS median household income data

- “Key Budget Policy Choices,” TCI, Feb 2019

- Virginia Medicaid Manual Ch. M02, DMAS, Oct 2018

- Virginia member request budget amendments 303 #8s and 303 #36h, 2019 session

- Emergency medicaid match rate is the regular match rate (50/50 in Virginia): https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/ss/ssema.pdf

- FIS for SB1200 (2019), Virginia Dept of Planning and Budget

- TCI and Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group data

- FIS for SB1200 (2019), Virginia Dept of Planning and Budget

- FIS for HB1461 (2019), Virginia Dept of Planning and Budget