June 27, 2019

Ten Years Behind: The Vital Role of Non-Instructional Staff in Promoting Successful Learning Environments and the Critical Need for Funding

Productive, safe learning environments where all students have the supports and resources to be successful depend on having sufficient staffing. Whether that is teachers and aides instructing students in the classroom, principals and assistant principals ensuring the appropriate management of the school, counselors and social workers assisting students with academic, social, and emotional learning outside of the classroom, or maintenance and transportation staff that keep facilities functional and get students to and from school safely.

Gov. Northam and state legislators can help ensure that students receive the support they need by undoing a policy decision made a decade ago to artificially cap investment in critical support positions.

Both instructional and support staff play vital roles in the safety and success of students. Yet since the 2008-2009 school year, there has been a profound drop-off in state investment for support staff positions. This is because in 2009, in response to the Great Recession, Gov. Tim Kaine and the legislature at the time agreed to add language to the budget that would put in place what was called a “cap” on support staff funding, cutting hundreds of millions in state funding for support staff.

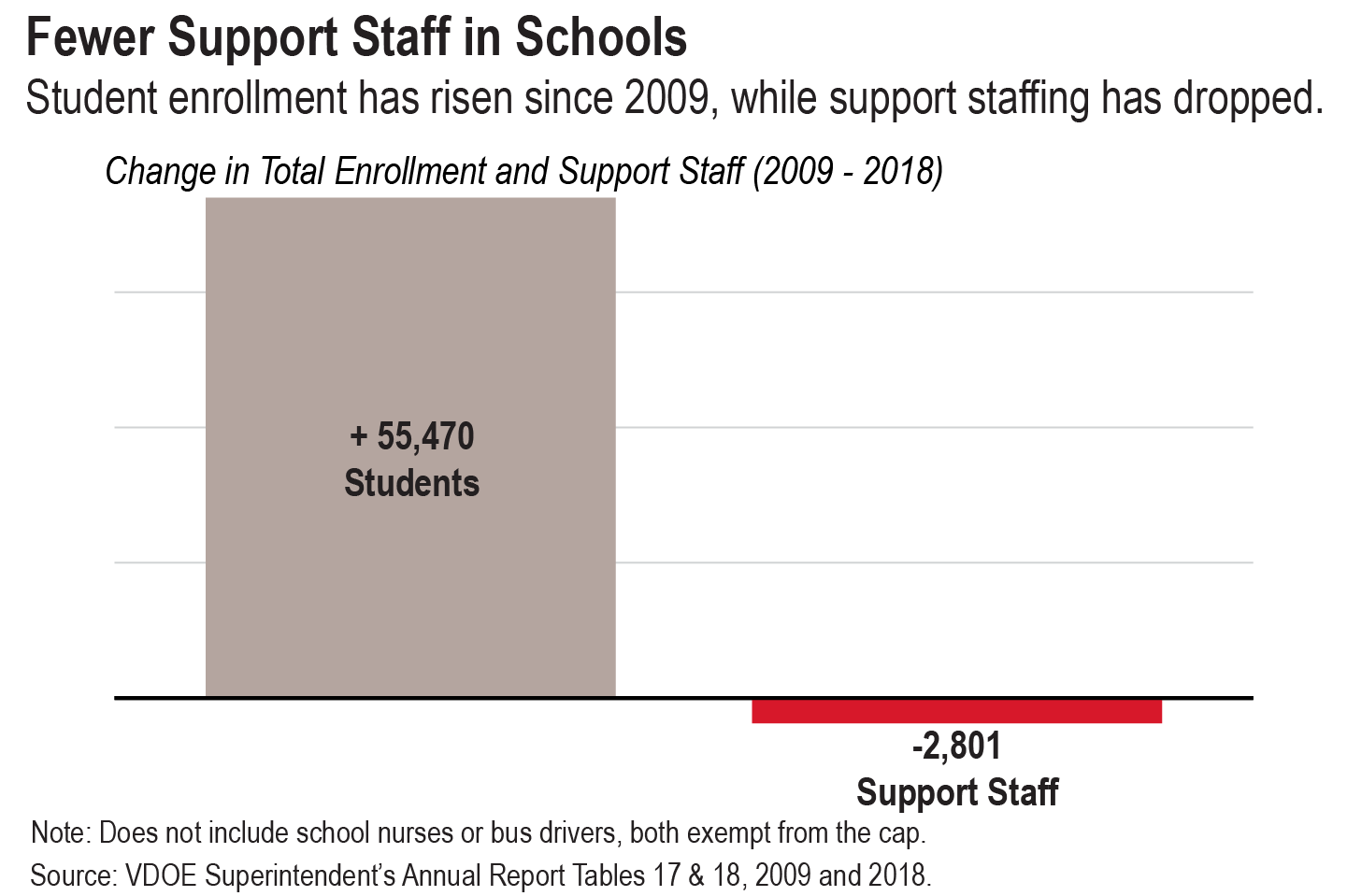

While student enrollment has increased by 55,000 students since that time, under the cap, support staff has decreased by 2,800 positions across the commonwealth (excludes school counselors, nurses, and bus drivers; not included in cap).1 These reductions mean school counselors have taken on administrative and testing responsibilities while maintaining large caseloads, and custodial staff has been drastically reduced to the point where schools do not have the capacity to maintain clean, healthy environments. It also means that instructors are forced to wear the hat of social worker, administrator, and custodian, and students are left without access to vital support services and facilities without proper upkeep.2

While student enrollment has increased by 55,000 students since that time [2009], under the cap, support staff has decreased by 2,800 positions across the commonwealth

A decade later, the recession has gone, state revenues have recovered, yet the support cap persists. Its impacts continue to be felt by school divisions across the commonwealth.

The students that feel these impacts most are those who may not have access to these supports, such as counseling, career development, and mental health services, outside of the school. Children and young adults of color are less likely to have access to mental health care, despite similar levels of need.3 If schools do not have these critical positions or caseloads are unmanageable, these children may never receive treatment. Support positions are vital for addressing and improving challenges that are particularly felt by students from low-income families and students of color such as chronic absenteeism, high rates of suspensions and expulsions, and overall school climate. Adequately addressing these challenges would lead to better academic and life outcomes for students.

The lack of adequate support staff in Virginia’s schools speaks to the importance of the state budget and how changes in policy language — even when they appear technical or obscure — shape our everyday lives. With the capacity to adequately fund these positions, the solution is simple: when Gov. Northam and state legislators put forward their budget proposals, they should leave out the three sentences in the budget that impose this harmful restriction on vital support positions and include the appropriate funds to ensure all schools have adequate staffing for safe, productive learning environments.

Impact of the Support “Cap” Statewide and by School Division

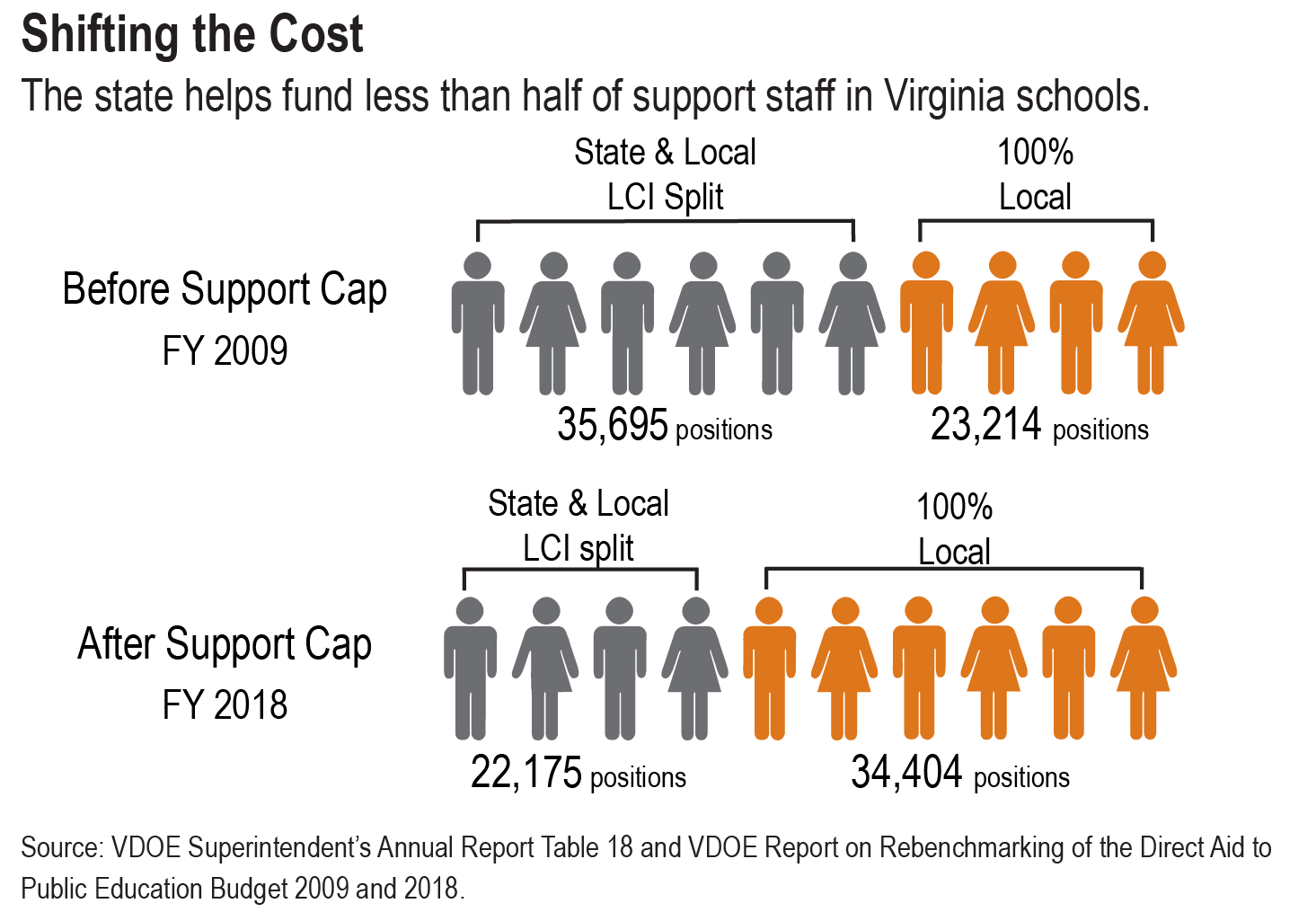

In the first year that the cap was implemented, the state cut funding for salaries and fringe benefits for support staff by $347 million.4 Almost 13,000 support positions lost state funding, forcing local governments to eliminate or fully fund these positions on their own.5

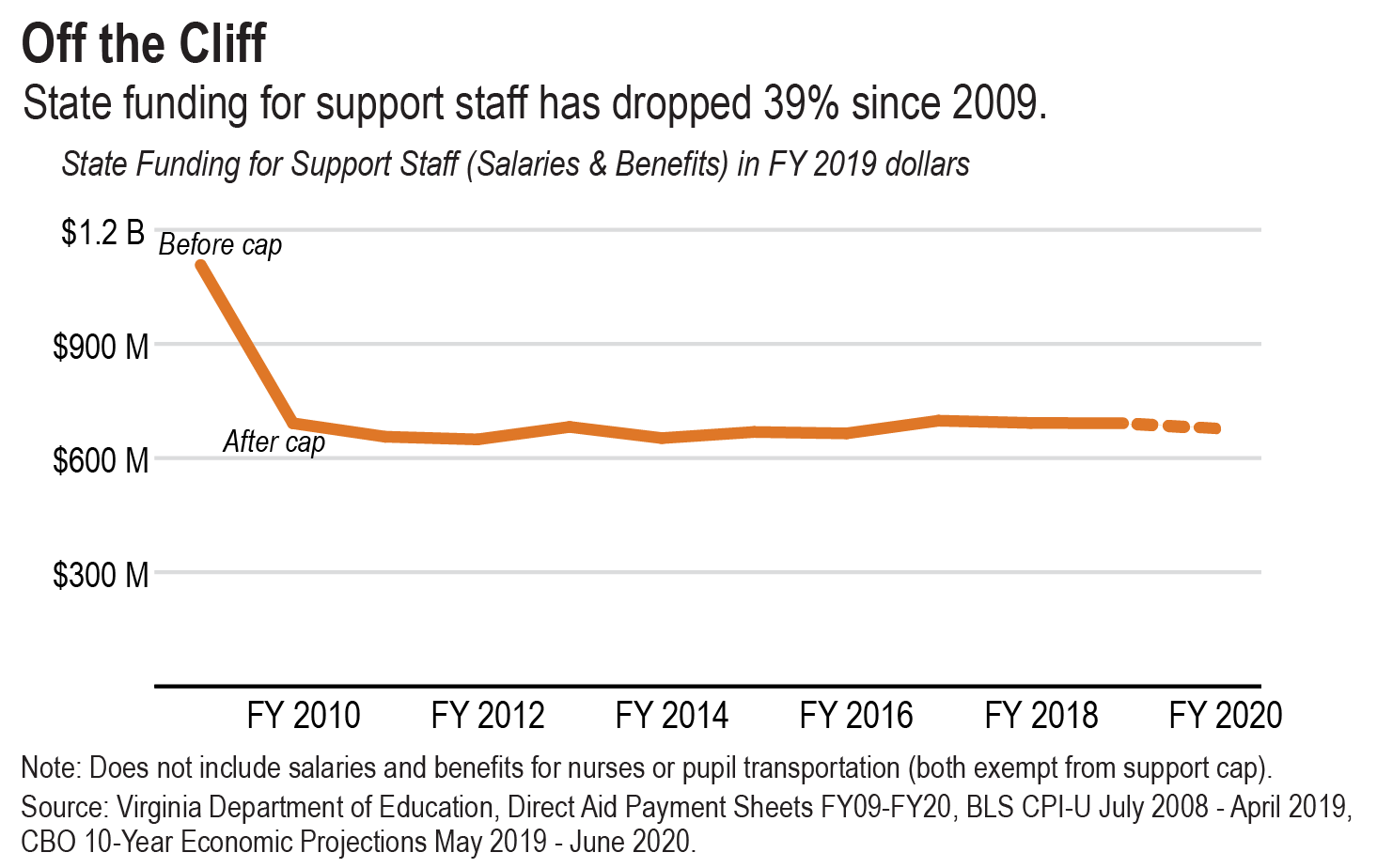

While pitched as a temporary strategy to save funding in a time of financial strain, the support cap has been included in every budget since its introduction 10 years ago. The impacts of the cap will continue through fiscal year 2020 with the approval of the latest state budget. State funding for support staff (salaries and benefits) will be down by $430 million this upcoming school year — a 39% decline — from what the state spent in 2008-2009, adjusted into 2019 dollars.6 The overall impact of these reductions over the past decade reaches more than $4.7 billion, adding up the annual reductions from 2010 to 2020.

Looking at individual school divisions, state funding for support staff has declined in 2019 dollars for 130 of Virginia’s 132 school divisions since the cap went into place. For many school divisions, the reduction is quite significant. The decrease in inflation-adjusted funding exceeded 50% — meaning the state now pays less than half as much in salaries and benefits as it did in 2008-2009 — for 39 Virginia school divisions. For the two divisions that have seen increased support staff funding (Loudoun County and Fredericksburg), those gains have been driven by a combination of their state and local cost share (local composite index) shifting and enrollment growth.7 Most divisions have not been so fortunate.

While reductions in state funding have been fairly universal, the impacts in terms of actual staffing have been more varied. School divisions with the highest share of students of color have seen their staffing levels drop more rapidly than other divisions with the lowest share of students of color. Support staffing dropped by 4 positions per 1,000 students in divisions with the highest percentage of students of color compared to a decrease of 1 position per 1,000 students in divisions with the lowest percentage. In total, support staff declined by more than 600 positions in divisions with the most students of color, while enrollment has grown by almost 16,000 students.8

The share of support positions the state helps pay for dropped to less than 40% since the implementation of the cap.9 This means that the state does not provide funding for six out of every 10 support positions in Virginia schools. It also means that every time the state offers a pay raise, like the 5% increase budgeted for the 2019-2020 school year, there are no state dollars available to local divisions to provide that raise for the majority of support staff in their schools. That is because the state only provides funding for support staff under the cap, or as its phrased in the budget, for Standards of Quality (SOQ) funded positions.10 This leaves local governments with a difficult choice: a) only provide a pay increase to some, not all support staff; b) only provide a partial pay increase to all support staff; or c) find the local revenues to fund a full pay increase to all staff.

The share of support positions the state helps pay for dropped to less than 40% since the implementation of the cap. This means that the state does not provide funding for six out of every 10 support positions in Virginia schools.

Understanding Virginia’s Support Cap

While commonly referred to as a cap, this policy is perhaps more accurately described in the Appropriation Act as “a funding ratio methodology.” It is not a flat cap that has remained steady since 2010, nor is it based on how many support staff schools have or need. Rather, it is a ratio of instructional staff to support staff. The inputs to the equation get updated every two years as part of the rebenchmarking process, resulting in a new funding ratio. It has gotten more stringent every update since its implementation in 2010,11 making it function more like a ratchet that continues to put tighter financial restraints on localities.

When the support cap was first implemented in 2010 that ratio was 4.03 — this meant that on average the state had a little more than four instructional staff for every one support staff. The minimum number of instructional staff required by Virginia’s Standards of Quality (SOQ) is then divided by this ratio number in order to determine state funding for support staff. This methodology creates a feedback loop where the cap pressures school divisions to decrease support staffing. As they do, the ratio and the severity of the cap increases. As evidence of this, the funding ratio has increased every time it has been updated, growing from 4.03 to 4.27,12 and will continue to grow unless state lawmakers take action.

In addition to being harmful, this calculation is flawed because the minimum instructional staffing ratios required in the SOQ are not designed to determine levels for support staff. These ratios developed by the Board of Education determine how many teachers, principals and counselors are needed to properly educate and advise students in the classroom. These standards do not show how many custodians are needed to maintain a functional and safe learning environment or how many accountants are needed to keep a school’s finances in order.13

In other words, the cap is arbitrary. It does not represent actual costs, and it is not based upon estimates of the number of needed support staff.

Prior to 2010, the SOQ formula estimated the cost of support staff using a more accurate approach. The formula calculated the most typical level of spending by school divisions on support staff. This way, the state paid schools based on typical levels of staffing and did not compensate schools for potentially excessive support costs. In a 2004 review of best practices in support services, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission concluded that “school division practices and expenditures for non-instructional support services in Virginia appear to be neither inadequate nor excessive.”14 The report noted that Virginia’s per-pupil expenditures for non-instructional services were below the national average and similar to the average for the southern region.

The state’s cap on funding support positions is not only arbitrary in its formula, but was also unnecessary to begin with because spending was appropriate.

Going Forward

Back in 2009, a student at the University of Virginia testified before the Virginia Board of Education against the support cap saying, “It is not a temporary solution to current economic hardships. Instead, it is a permanent reduction in the Standards of Quality which will outlast the current recession.”15 A decade later, we continue to see the wisdom of those words. What was presented as a temporary cost reduction has become part of the budgeting process — just the cost of doing business.

Yet it does not have to be this way. Virginia is in the midst of economic growth with new revenues coming into the state. We are a top 10 state in the country in median household income, yet bottom 10 when it comes to the state investment in K-12 education.16 The capacity exists for lawmakers to fully fund support positions in our schools whether they decide to use existing revenues (from our continued economic growth, new online sales tax collections, and additional collections from conforming to federal tax legislation) or find new revenue streams. Lawmakers could look to modernize the state’s corporate income tax system by passing “combined reporting” laws to ensure large, multi-state corporations do not shift profits earned in Virginia to other jurisdictions and thereby ending a tax advantage that local businesses do not get.

There is a clear path forward for lawmakers to fully fund support positions in Virginia schools. Gov. Northam can direct the Virginia Department of Education to remove the funding cap on support positions from the biennial rebenchmarking process, and the governor and General Assembly can leave out the item in the state budget maintaining that cap. Doing so will help lift a decade-long shadow over our schools cast by the Great Recession, ensure schools have the appropriate staffing for safe, productive learning environments, and support students across the commonwealth.

More from this report

Endnotes

- TCI analysis of Superintendent’s Annual Report Tables 17 & 18, Virginia Dept. of Education (VDOE) FY09-18 (excludes “Administrative, Attendance and Health – Other Professional” and “Transportation – Trades, Operative and Service”)

- Duncombe, C., Gilliam, Jr., K., and Cassidy, M., “Demonstrated Harm,” TCI, 2017

- Marrast, L., Himmlestein, D., and Woolhandler, S., “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Care for Children and Young Adults: A National Study,” International Journal of Health Services, 2016

- TCI analysis of Direct Aid Payment Sheets, “Basic Aid” worksheet, VDOE, FY09-10

- TCI analysis of Superintendent’s Annual Report Table 18, VDOE, FY09-10

- TCI analysis of Direct Aid Payment Sheets, “Basic Aid” worksheet, VDOE, FY09-20 and CPI-U, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 08-19 and 10 Year Economic Projections, Congressional Budget Office, 19-20

- TCI analysis of Composite Index of Local Ability to Pay, VDOE, FY09-20 and Direct Aid Payment Sheets, “Adjusted ADM,” VDOE, FY09-20

- TCI analysis of Superintendent’s Annual Report Tables 17 & 18, VDOE, FY09-18 and Fall Membership Reports, VDOE, 18-19

- TCI analysis of Superintendent’s Annual Report Table 18, VDOE, FY10 and Report on Rebenchmarking of the Direct Aid to the Public Education Budget for the 2010-2012 Biennium, presentation from VDOE to the Virginia Board of Education, July 2009

- Virginia’s 2018-2020 Budget, Chapter 854 Item 136

- Report on Rebenchmarking of the Direct Aid to the Public Education Budget, presentation from VDOE to Virginia Board of Education, July 2009, July 2011, Sept. 2013, Sept. 2015, Sept. 2017

- Ibid.

- Duncombe, C. and Cassidy, M., “Eroding Standards,” TCI, 2016

- “Best Practices for the Support Services of School Divisions,” Joint Legislative Audit and Review Comm., 2004, pg. II

- Moela, O., “Board of Education examines data on school support staff,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 2009

- Goren, L., Wodicka, C., Duncombe, C., and Mejia, F., “Standing at the Crossroads,” TCI, 2019