December 12, 2019

Raising the Wage in Virginia Will Benefit Working Families

Executive Summary

Everyone in Virginia working a full-time job should be paid enough to provide for their family. However, for many this is not the case. Nearly two-thirds of Virginia families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold have at least one adult who is working, yet they are paid too little to make ends meet. Virginia policymakers could raise the wages of working people in Virginia and help families across the commonwealth by raising Virginia’s minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024, closing loopholes that currently exclude many Black and Latinx workers, and making sure Virginia’s wage laws are fairly enforced.

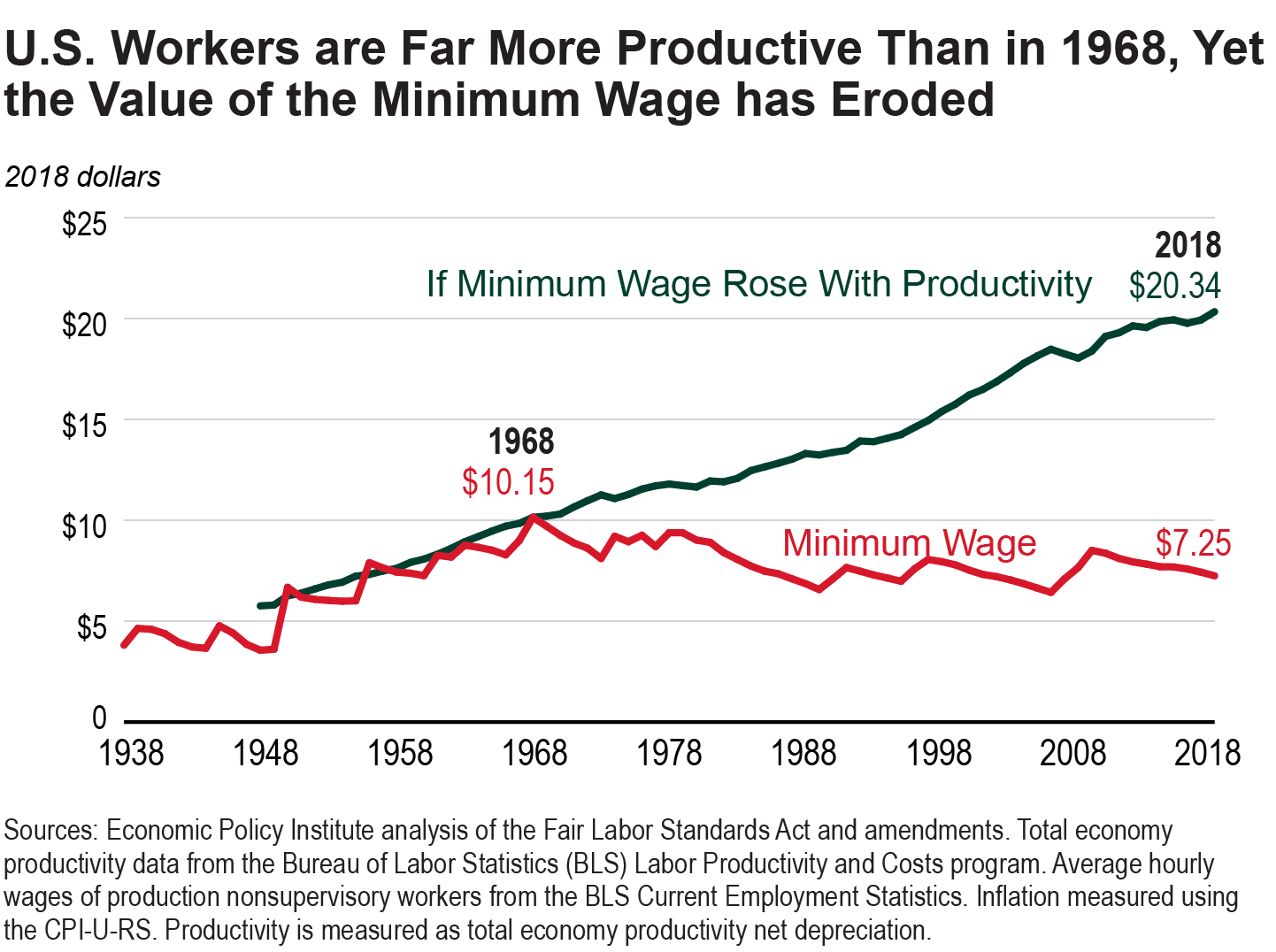

The federal minimum wage has eroded significantly since the late 1960s compared to the typical cost of living, median wages, and the economic productivity of working people. Virginia’s current minimum wage, set at $7.25 an hour to match the federal minimum, is the lowest in the country compared to the typical cost of living in the state, according to OxFam’s State of Working America report. The choice to maintain this inadequate minimum that leaves many families behind is a part of a pattern in Virginia of policymakers failing to act to protect working families and instead too often erecting barriers to success, particularly for working families of color. This erosion in the minimum wage has particularly harmed Black and Latinx working people. This is because working people of color in Virginia are more likely than white workers in Virginia to be stuck in low-wage occupations due to ongoing job discrimination, lack of educational opportunities, and other barriers that white people in Virginia are less likely to have faced.

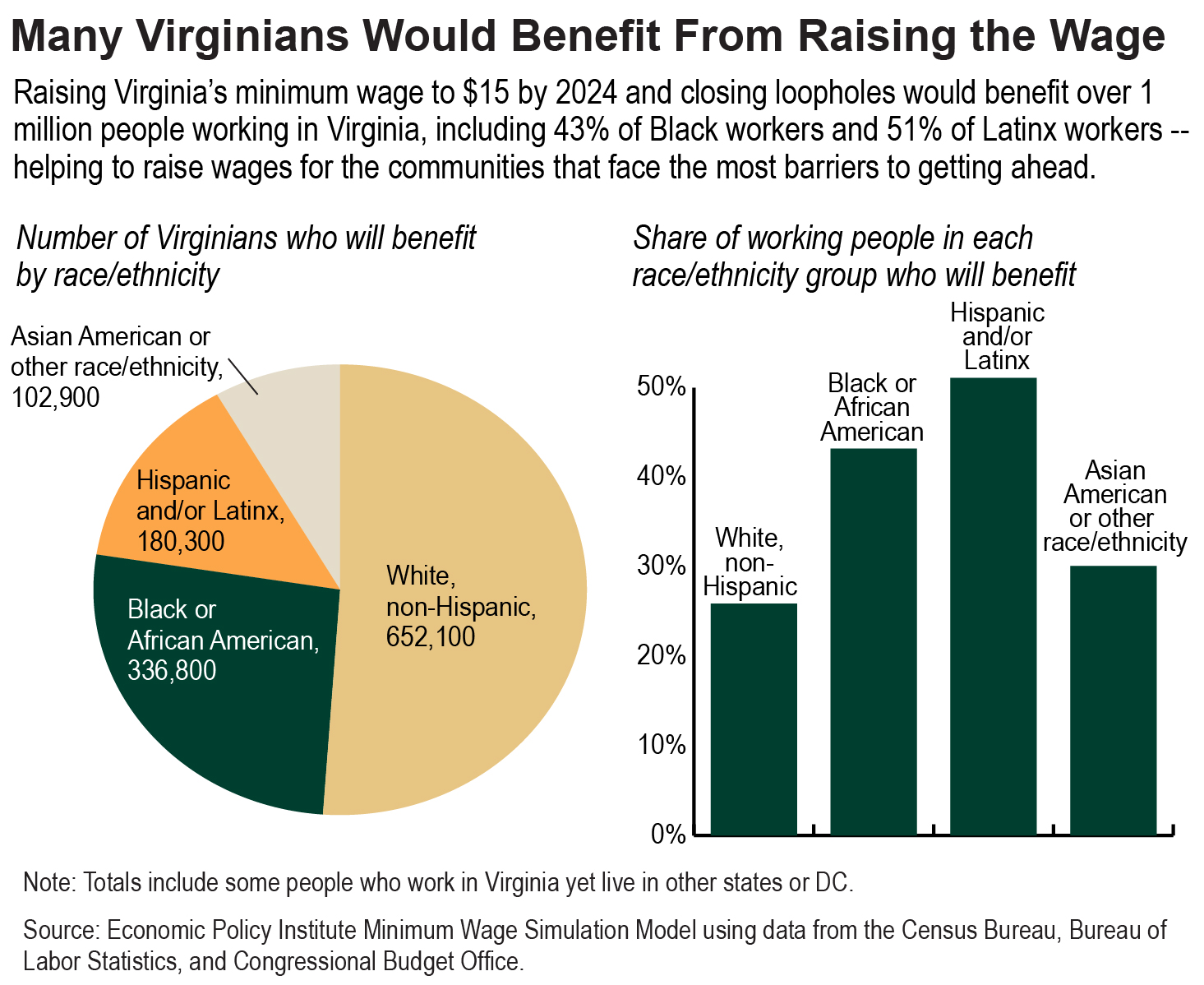

1,272,000 people working in Virginia would benefit from raising the wage to $15 by 2024, including:

- 1,167,000 adults ages 20 and older

- 774,000 full-time workers

- 751,000 women

- 620,000 workers of color

In 2020, Virginia policymakers can and should make new choices that will help the very people and families in Virginia that have faced the greatest barriers. Raising the wage to $15 an hour by 2024 would help 1 in 2 women of color who are working in Virginia. And the vast majority of those who would benefit are full-fledged adults who are working at least 20 hours a week, many with at least some college education.

In addition, recent studies of the effects of the minimum wage find little to no job losses and significant benefits for workers who are paid low wages, including higher wages, higher total incomes, and lower poverty rates. The effect of raising the minimum wage is one of the most heavily studied topics in economics, and most recent studies that use the highest-quality research designs have concluded that past increases in the minimum wage have had little to no effect on employment levels. For example, in a January 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Doruk Cengiz and co-authors studied 138 state-level changes in the minimum wage between 1979 and 2016 and found “the overall number of low-wage jobs remained essentially unchanged over five years following the increase.”

In spite of barriers and challenges faced by Virginia families, people have historically and successfully been able to come together to make public policy work better for all of us. This includes Black and white families who came together to win state funding for a system of free public schools in 1870, the fight by Black students in the 1950s to make sure they had access to decent school buildings and textbooks, and the successful work by Black, Brown, and white families across the commonwealth to win broader access to health care through Medicaid expansion in the 2010s. Coming together again to raise the minimum wage would be a step in the right direction for working families across the commonwealth, including those Black and Latinx families who face the biggest barriers today.

How we got here

Virginia history of oppression related to wage policy

Significantly raising the minimum wage, closing loopholes, and strengthening enforcement would be a major change in public policy direction in Virginia. Despite the progress made by courageous Virginia families coming together over the centuries to work for a better commonwealth, the dominant thread in Virginia’s history has been using public policy to protect the interests of political and economic elites, including suppressing the workplace and political organizing of working people who are seeking to raise their wages. And a central element to this strategy has been using created racial hierarchies to maintain the exploitation of Black workers.

As a result of exclusionary housing and employment practices, racist violence against Black organizers, the systematic underfunding of education, and mass incarceration, Black Virginians have often been prevented from successfully organizing to raise their wages, competing for higher-paid “white” working-class jobs, or obtaining advanced educations to compete for professional jobs. In addition, Virginia elites have effectively suppressed unionization in Virginia through laws and ideological campaigns, thereby preventing working people in Virginia from raising their wages through collective bargaining. This is not to say that no progress has been made over time and that no individual Black Virginians have been able to overcome these extra barriers, but far too often, Black Virginians and, more recently, Latinx Virginians have faced barriers to advancement and have been stuck in low-wage occupations with little ability to gain better pay. While there was progress between 1980 (the first year for which comparable data is available) and the mid-1990s in narrowing the wage gap between Black and white Virginians, most or all of that progress has been lost — in 1980, Black workers in Virginia were paid 70 cents for every dollar paid to white workers; in 2018 it was just 71 cents.

Far too often, Black Virginians and, more recently, Latinx Virginians have faced barriers to advancement and have been stuck in low-wage occupations with little ability to gain better pay.

As a result of this capturing of political and ideological power by elite white Virginians, Virginia has few laws to protect and uplift working people. Virginia has no overtime law except for a few public safety employees; does very little to enforce worker health, safety, and labor protections; has failed for a decade to raise its minimum wage above the low federal base; and has excluded most historically Black occupations from coverage in the minimum wage law. Some of the most egregious exclusions were removed by the General Assembly in 2019, yet many remain, including the exclusion of all domestic and agricultural workers from minimum wage protections.

Federal minimum wage, its exclusions, and fights to reduce those exclusions

While Virginia’s legislature has rarely prioritized the interests of working people, federal policy has stepped in at times to offer some baseline protections. Working people of color, however, have had to fight to be included in the full benefits of these policies, and there is more that should be done to make sure every working person receives the full protections of minimum wage laws and other worker protections. The federal minimum wage was established in 1938 as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), yet the act excluded from the minimum wage and other protections many agricultural, domestic, and service workers, occupations that at the time were the only jobs available to many Black people, particularly in the south, and today continue to be more likely to employ Black and Latinx workers. As a result of people coming together to demand fairer wages, many of these exclusions were finally removed at the federal level in 1967, resulting in the extension of minimum wage protections to previously excluded sectors where nearly one-third of Black workers and one-fifth of white workers were employed.

Between 1938 and 1968 there were also regular adjustments to the value of the minimum wage to make sure that it kept up with improvements in typical wages and the productivity of U.S. workers. This helped make sure that working people saw a fair share of the value they created. As a result, in 1968 the minimum wage was just over one-half of typical (median) wages for full-time, year-round workers and was about one-third the net productivity (average output per hour worked) in the overall economy. Combined with the inclusion of a larger share of the workforce, these adjustments helped make sure that a full-time, year-round worker could provide a modest but decent standard of living for a small family.

Erosion of federal minimum wage since 1968

Although people successfully came together between 1938 and 1968 to remove some of the exclusions from the minimum wage and make sure it kept up with the growing productivity of U.S. workers, since 1968 the federal minimum has dramatically weakened compared to cost of living, typical wages for middle-class workers, and the productivity of workers. As a result, the minimum wage is just 32% of typical national wages (down from 53% in 1968) and is just 11% of net productivity (down from 34% in 1968). This erosion has particularly disadvantaged communities of color – poverty rates for Black and Latinx families would be almost 20% lower had the minimum wage remained at its 1968 inflation-adjusted level, and would be even lower if the minimum wage had kept up with increases in productivity or median wages.

Policy proposal and who would benefit

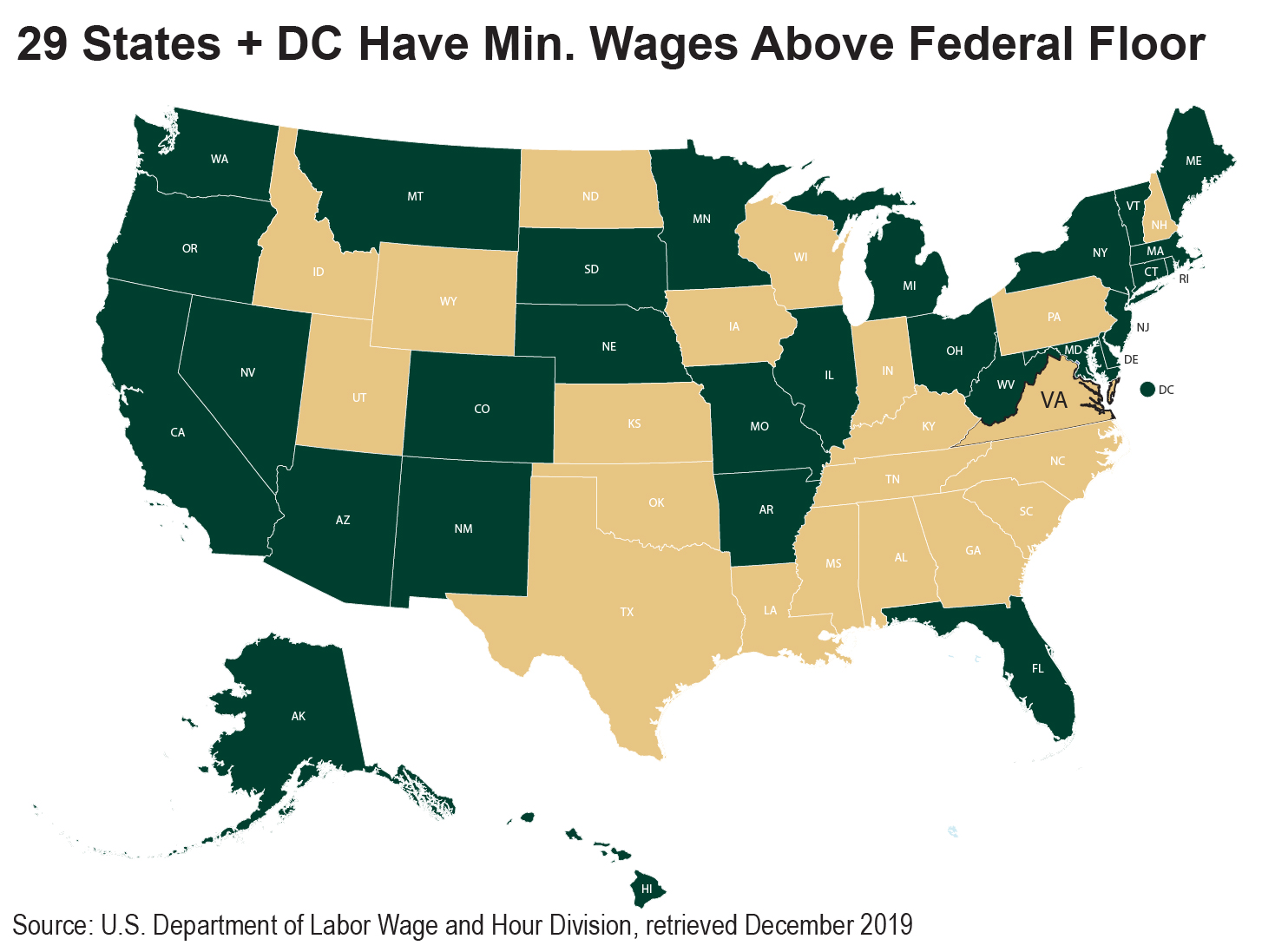

As of October 2019, 29 states and D.C. have minimum wages above the federal minimum, including Virginia’s neighboring states of West Virginia and Maryland. There are also 33 states plus D.C. that set a base wage for tipped workers above the federal minimum of $2.13 an hour (Virginia has no base wage for tipped workers). Many of the states that have established minimum wages and base wages for tipped workers above the federal floor have done so using phase-in schedules and then annual adjustments for cost of living increases. While the federal FLSA establishes a floor for what employers can pay in most situations, given the inaction of the federal government on keeping the minimum wage at a reasonable level compared to the cost of living, typical wages, and productivity, more and more states are acting to set minimum wages above that inadequate federal floor.

$15 by 2024 compared to productivity growth and median wages

Raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would help reverse the erosion in the value of the minimum wage since 1968 compared to productivity and typical wages, making sure that working people see a fairer share of the benefits from their work. Virginia’s minimum wage level is currently set by law to be the same as the federal baseline despite Virginia having a robust economy and higher-than-typical cost of living, especially related to housing costs. As a result, Virginia’s minimum wage is the lowest in the country compared to the cost of paying for rent, groceries, transportation, child care, and other necessities. This contributes to Virginia’s last-in-the-country ranking on OxFam America’s list of “Best States to Work.”

In 1968, the minimum wage was 53% of median hourly wage. Today, the federal minimum wage — and therefore the Virginia minimum wage — is just 29% of the median hourly wage in Virginia. Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024 would raise it to 52% of the Virginia median wage, a similar level to the 1968 federal minimum compared to the national median wage (Virginia-specific median wage data for 1968 is not available).

How many workers would benefit by race, gender, and age

Raising the minimum wage in Virginia to $15 an hour by 2024, removing the “Jim Crow”-era exemptions that were intentionally designed to leave out Black workers, and providing a base wage for tipped workers would benefit over 1.2 million people who are working in Virginia. This includes directly raising wages for about 1,018,000 working people who would otherwise make under the new minimum wage. It also includes indirectly boosting wages for another 254,000 who make just above the new minimum and would see boosts as employers seek to maintain wage scales and reward seniority, according to new microdata analysis by the Economic Policy Institute prepared for this report. That’s about 1 in every 3 working people in Virginia.

The vast majority of Virginians who would benefit are working adults helping to support themselves and their families — 92% are age 20 or older and 89% are working at least 20 hours a week. Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024 would help 1 out of every 2 women of color employed in Virginia, thereby boosting the wages of those Virginians who have historically been excluded from opportunities to work in well-paying jobs and have seen the jobs they do have devalued precisely because they are filled by women of color.

And while about half of all people working in Virginia who would benefit are white, working people who are Black or Latinx are more likely than their white counterparts to currently be paid low wages and therefore benefit from a higher minimum wage. While 26% of white workers in Virginia would benefit, 43% of Black workers and 51% of Latinx workers would directly or indirectly benefit. And about 30% of Asian American workers and workers of other racial identities would benefit from raising the minimum wage (these categories are combined in the available data due to sample size limitations). This is because working people of color in Virginia are more likely than white workers in Virginia to be stuck in low-wage occupations due to ongoing job discrimination, lack of educational opportunities, and other barriers that white people in Virginia are less likely to have faced.

Additional information on how many working people in Virginia will benefit from raising the wage to $15 an hour and closing loopholes can be found in the Appendix of this report.

Tipped workers

Virginia is currently the only state in the entire country that has a minimum wage yet has no required “base wage” for tipped workers, which means that as long as tips are sufficient to boost overall pay to above the minimum wage level, employers are not required to pay their workers anything under Virginia law. (Many tipped workers in Virginia are covered by the federal minimum wage law, which requires a “base wage” of $2.13 an hour.) Furthermore, Virginia law allows employers to determine the amount of tips workers receive in determining whether the overall pay (including tips) is above the minimum wage. If a potential issue arises, tipped workers must prove by “clear and convincing evidence that the actual amount of tips received by him was less than the amount determined by the employer.” This puts the burden of proof on tipped workers to prove that they are being paid less than the minimum wage, rather than requiring employers to prove they are reaching at least the minimum wage. And contrary to some assumptions, the vast majority of tipped work is low-paying, with typical hourly earnings (including tips) of just $11 an hour.

As policymakers consider raising Virginia’s overall minimum wage, tipped workers should be included in the policy change to make sure that these workers, 71% of whom are women, are also paid a fair wage. Women of color are particularly likely to work in tipped occupations — 31% of tipped workers living in Virginia are women of color, a higher share than the 19% of all working Virginians who are women of color. Creating a base wage in Virginia for tipped workers will make sure every working Virginian is paid something by their employer. And tying the base wage for tipped workers to the full minimum wage by defining it as some fraction of the full minimum will help make sure tipped workers benefit as the overall minimum wage rises. For example, setting the base wage for tipped workers at 70% of the standard minimum wage will boost the pay for about 104,000 tipped workers in Virginia by 2024, the majority of whom are women.

Broader benefits for families and local economies

A $15 minimum wage would make a significant difference in the lives of many working people in Virginia. Annual income for year-round workers who would be impacted by the increase would rise by an average of about $4,400 in 2018 dollars, an increase of 20% over how much they would make with no minimum wage increase. That’s money that working families with low incomes can use to pay the rent, make needed car repairs, and buy back-to-school supplies. And raising the wages of families with low incomes — who tend to spend most of their income in their own communities rather than on vacations abroad or being able to save for future generations — will help support more spending at local businesses.

Annual income for year-round workers who would be impacted by the increase would rise by an average of about $4,400 in 2018 dollars. That’s money that working families with low incomes can use to pay the rent, make needed car repairs, and buy back-to-school supplies.

Raising the minimum wage will also help lift poor working families above the poverty line, a change that will help children grow up in families with less stress and more stability. Over three-fifths of Virginia families with incomes below the poverty threshold have at least one adult in the household who is working. As a result, there are around 266,000 working adults living in Virginia households with incomes below the poverty threshold, which is just $25,465 for a married couple with two children. And Virginians who are Black or Latinx continue to be more likely than white and Asian American Virginians to have incomes below the poverty line. This is not by chance – state policymakers have chosen to perpetuate historical inequities by blocking attempts to raise Virginia’s minimum wage to more reasonable levels, by not adequately funding schools in high-poverty communities, and by denying many immigrants access to driver’s licenses, among other policy choices. Raising the minimum wage will help to reverse this: while $7.25 an hour for a full-time, year-round worker is too little to support even a family of two at the poverty level, $15 an hour is enough to lift most working families with a full-time, year-round worker above the poverty line. Even with a $15 an hour minimum wage many families will still struggle to afford the basics due to the high cost of childcare and housing in many areas of Virginia, but at least they will have more of a fighting chance.

Well-meaning fears about job loss are misplaced

The effect of raising the minimum wage is one of the most heavily studied topics in economics, particularly since the 1990s. Most recent studies that use the highest-quality research designs have concluded that past increases in the minimum wage have had little to no effect on employment levels. For example, in a January 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, researchers studied 138 state-level changes in the minimum wage between 1979 and 2016 and found “the overall number of low-wage jobs remained essentially unchanged over five years following the increase.” Importantly, this study included increases in the minimum wage up to 55% of the state’s median wage and found no negative employment effects even up to those levels; the proposed $15 minimum wage by 2024 is below that level as a share of Virginia’s median wage. And a 2016 meta-analysis of 37 published minimum wage studies from 2000 to 2015 — essentially, a quantitative summary of all the other literature in the field — found “no support for the proposition that the minimum wage has had an important effect on U.S. employment.”

And meaningful changes in the minimum wage have been done before in the southern United States without negative employment effects. Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024 will benefit a significant share of working people in Virginia, yet it is not unprecedented in the share of workers who are benefited. The 1967 extension of the Fair Labor and Standards Act (FLSA) to the agricultural, hotel, restaurant, and other sectors that were large employers in the south, and where Black workers represented over a third of the workforce, resulted in large gains in wages for Black workers without any negative effects on employment levels for either Black or white workers.

Taking a step back, the narrow focus on the overall number of jobs or hours worked is a flawed way of measuring the impact of minimum wage increases, because what matters to low-wage working people is their total income throughout the year. Even those low-wage workers who may see a reduction in hours or even lose a job are likely to be better off with a higher minimum wage over the course of the year. That’s because frequent turnover in low-wage occupations means most low-wage workers already typically hold multiple jobs over the course of a year, and the higher wages will more than offset the reduction in hours for most impacted workers, resulting in an increase in total annual earnings.

The narrow focus on the overall number of jobs or hours worked is a flawed way of measuring the impact of minimum wage increases, because what matters to low-wage working people is their total income throughout the year.

Even after factoring in possible employment losses, a number of studies have shown significant increased overall earnings for low-wage working people and reductions in poverty rates from raising the minimum wage. That’s likely due to the substantial benefits for the vast majority of low-wage working people who retain their jobs and, for those who do lose a job, the likelihood that over the course of a year increased earnings from other jobs would offset the loss. For example, the recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report that relies heavily on studies of just a few minimum wage increases rather than high-quality analyses of all recent minimum wage increases provides estimates that a national $15 minimum wage would result in some job losses. Yet if those estimated losses are compared to the number of workers who would be impacted by minimum wage increases, basic math shows that 95.5% of all impacted workers would remain employed and would see sizable wage increases, with many of those workers who do lose jobs finding another one within a short time. As a result, even after accounting for their expectations of employment losses, the data in that CBO study shows that average annual earnings would increase by $1,500 for impacted workers. This is especially good news for Black and Latinx workers who are more likely than white workers to currently be paid under $15 an hour.

Raising the wage for public employees

Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour will also benefit state and local employees, and although this will introduce some new costs to the state and localities, the benefits to working families are substantial compared to the impact. A recent study by The Century Foundation found that about one-third of local government employees in the United States might see a raise from a national $15 minimum wage phased in by 2025. Yet the study also found that because many of these workers already make close to the new thresholds, the annual cost of increases as a share of overall payrolls would be substantially less than the typical annual cost of raises between 2013 and 2017. In Virginia, local school employees had median wages of $22.49 in 2017 and non-school local employees had median wages of $21.44, and in both cases about 1 in 3 local employees would see a raise from an increase in the minimum wage to $15 by 2025. And in both cases the annual cost of raises to lift local employees to the new minimum wage would be about 1.1% of total payroll, well below the annual pace of payroll increases between 2013 and 2017.

About 1 in 3 local employees would see a raise from an increase in the minimum wage to $15 by 2025. The annual cost of raises would be about 1.1% of total payroll, well below the annual pace of payroll increases between 2013 and 2017.

The state minimum wage should lift families in all parts of the commonwealth

Virginians across the commonwealth work hard and deserve to be paid a fair wage. Nowhere in the commonwealth is the current minimum wage sufficient to reasonably pay the bills of even a childless adult, and a universal $15 wage floor will help lift families across the commonwealth. And despite some fears, research shows that doing so is unlikely to have significant negative job impacts. A recent study of the effect of raising the minimum wage in counties and other small areas where the new minimum is a high share of the overall typical (median) wage found positive impacts on wages, a reduction in household and child poverty rates, and no adverse effects on employment, weekly hours, or annual weeks worked. The same study also looked specifically at some of the groups of workers who are most impacted by raising the minimum wage (women, Black, and/or Hispanic workers) and found no adverse employment for any subgroup, even in these low-wage areas of the country.

There may be a need for a minimum wage that is higher than $15 in high-cost parts of Virginia. Along with setting a statewide wage floor of $15 an hour to make sure no working Virginian is left with below-poverty wages, state policymakers should provide cities and counties with the authority to set higher wage floors as appropriate for their localities.

Importance of improving enforcement

Protections for working people have little meaning if they’re not enforced, and Virginia policymakers should strengthen the state’s wage enforcement policies and practices to make sure every eligible worker benefits from the new minimum wage. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of work to be done because Virginia currently does very little to investigate or prosecute wage theft complaints. The state agency that is supposed to investigate claims of wage theft has been so underfunded for so long that it is only able to fully investigate a fraction of the complaints it receives — a recent review by Legal Aid Justice Center found that in the past four years the Department of Labor and Industry (DOLI) rejected with no investigation whatsoever nearly half of the 4,000 wage theft allegations that they closed. For example, the Department rejects all complaints by tipped workers and sometimes rejects complaints just because the victim got help from a lawyer in filling out the complaint form. Other complaints are dismissed without full investigation, including in cases where the employer has never responded to the charges. This would be like if a city council decided it no longer had the resources to do even cursory investigations of convenience store robberies, so it just wasn’t going to assign any detectives to half of them. Virginia policymakers should provide adequate funding for DOLI’s wage enforcement efforts and DOLI should, in turn, investigate all complaints to the fullest extent possible.

Virginia policymakers should make other reforms to reduce wage theft in Virginia, including creating a right of private action for non-payment of wages so that people who are victims of wage theft can seek redress in court, prohibiting retaliation against employees filing wage theft claims, and allowing DOLI to review all payroll records at a particular employer if there is good reason to believe that multiple workers are being underpaid. These protections will help make sure that workers, particularly those who may be most marginalized and afraid to step forward, are not cheated out of the wages they have earned.

Each year that passes without action results in a less and less valuable minimum wage.

Conclusion

Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, closing loopholes, and ensuring fair enforcement would improve many lives across the commonwealth as many families would have greater confidence in being able to afford basic necessities, and would particularly help Black and Latinx workers who are more likely to be stuck in low-wage occupations and would see their incomes increase if policymakers act to make these improvements. This is an issue where urgency is needed. Each year that passes without action results in a less and less valuable minimum wage. Virginians have come together in the past to bring the Commonwealth of Virginia closer to attaining that aspirational name, and policymakers should act now to lift up working families and bring us a step closer to being a commonwealth for all, no exceptions.

Endnotes

- E.g., in 1888 the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals outlawed the tactic that labor and community organizers were most effectively using to win concessions from local elites, declaring that “that the right to boycott was ‘incompatible with the prosperity, peace, and civilization of the Country.’” For further discussion, see Carvalho, J., “The Baughman Boycott and its Effect on the Richmond, Virginia Labour Movement, 1886-1888,” Historie Sociale – Social History, Vol 12 No 24, 1979

- Anderson, P., “Supporting Caste: The Origins of Racism in Colonial Virginia,” Grand Valley Journal of History: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1, 2012, and Powell, J., “The Race and Class Nexus: An Intersectional Perspective,” 25 Law & Ineq. 355, 2007

- E.g., the response by local elites to organizing in Richmond by the Knights of Labor in the 1880s, as discussed in Miner, C., “The 1886 Convention of the Knights of Labor,” Phylon, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2nd Qtr., 1983), pp. 147-159

- TCI analysis based on Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

- TCI review of the Code of Virginia

- Marritz, N. and Elliot, K., “Getting Workers What They’re Owed,” Legal Aid Justice Center, Nov 2019, and Goren, L.,“Lawmakers Have the Chance to Protect Working Virginians,” The Commonwealth Institute, Apr 2016

- U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, “Changes in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-Farm Employment Under State Law: Selected Years 1968 to 2018,” retrieved Dec 2019

- Code of Virginia “§ 40.1-28.9”

- Ch. 330, Acts of Assembly 2019 “http://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?191+ful+CHAP0330”

- Perea, J., “The Echoes of Slavery: Recognizing the Racist Origins of the Agricultural and Domestic Worker Exclusion from the National Labor Relations Act,” 72 OHIO ST. L.J. l 95, 2011

- Agricultural: “Agricultural Worker Demographics” National Center for Farmworker Health, Inc., 2018

Domestic: Boyd, K., “The Color of Help,” Center for American Progress, Jun 2011 - Derenoncourt, E. and Montialoux, C., “Minimum Wages and Racial Inequality,” unpublished job market paper, Nov 2018

- Cooper, D., “Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would lift pay for nearly 40 million workers,” Economic Policy Institute, Feb 2019

- Ibid.

- Economic Policy Institute Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019. Dollar values adjusted by projections for CPI-U in CBO August 2019 projections.

- Zipperer, B., “The erosion of the federal minimum wage has increased poverty, especially for black and Hispanic families,” Economic Policy Institute, Jun 2018

- “Minimum Wage Tracker,” Economic Policy Institute, as of Oct 9, 2019

- Ibid.

- “State Minimum Wages | 2019 Minimum Wage by State,” National Conference of State Legislators, Jan 2019

- “Cost of Living Data Series, Third Quarter 2019,” Missouri Economic Research and Information Center, retrieved Dec 2019

- The Best and Worst States to Work in America “data appendix,” OxFam America, Jul 2018, retrieved Dec 2019

- “The Best and Worst States to Work in America,” OxFam America, Jul 2018

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model. Dollar values adjusted by projections for CPI-U in CBO August 2019 projections.

- Perea, J. “The Echoes of Slavery: Recognizing the Racist Origins of the Agricultural and Domestic Worker Exclusion from the National Labor Relations Act,” 72 OHIO ST. L.J. l 95, 2011, and Linder, M., “Farm Workers and the Fair Labor Standards Act: Racial Discrimination in the New Deal,” 65 Texas Law Review 1335, 1987

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model.This analysis assumes a minimum wage increase to $15 by 2024, that currently exempted agricultural and domestic workers will be covered by the minimum wage, and that the base wage wage for tipped workers will be raised in stages until reaching 70% of the overall minimum by 2025. The number of workers who would benefit includes all workers in Virginia, including a small number who live in other states and work in Virginia. Directly affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate exceeds their existing hourly pay. Indirectly affected workers have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and 115 percent of the new minimum). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Electronic communication from T. Gebreselassie at NELP dated Dec 9, 2019.

- Code of Virginia, “§ 40.1-28.9”

- Cooper, D., “Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would lift pay for nearly 40 million workers,” Economic Policy Institute, Feb 2019

- “Women in Tipped Occupations, State by State,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2019

- Ibid.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model.

- Ibid.

- TCI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2018 American Community Survey data.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model.

- Cengiz, D., Dube, A., Lindner, A., and Zipperer, B., “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs: Evidence from the United States Using a Bunching Estimator,” NBER Working Paper No. 25434, Jan 2019

- Ibid.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model.

- Wolfson, P. and Belman, D., “15 Years of Research on U.S. Employment and the Minimum Wage (December 10, 2016),” Tuck School of Business Working Paper No. 2705499

- Derenoncourt, E. and Montialoux, C., “Minimum Wages and Racial Inequality,” unpublished job market paper, Nov 2018

- Cooper, D., Mishel, L., and Zipperer, B., “Bold increases in the minimum wage should be evaluated for the benefits of raising low-wage workers’ total earnings,” Economic Policy Institute, Apr 2018

- For example, Dube, A., “Minimum Wages and the Distribution of Family Incomes.” NBER Working Paper no. 25240, Nov 2018, and Rinz, K. and Voorheis, J., “The Distributional Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data.” Working Paper 2018-02, Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications, U.S. Census Bureau, Mar 2018

- Zipperer, B., “Low-wage workers will see huge gains from minimum wage hike, CBO finds,” Economic Policy Institute, Jul 2019, providing analysis of, “The Effects on Employment and Family Income of Increasing the Federal Minimum Wage,” Congressional Budget Office, Jul 2019

- Parrott, J., “The Impact of Increased Minimum Wages on Local Governments,” The Century Foundation, Oct 2019

- The Century Foundation, data provided to TCI by request.

- Ibid.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model using data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office. Estimates provided to TCI by request. See EPI Minimum Wage Simulation Model 2019 for more information on the model.

- Godøy, A. and Reich, M., “Minimum Wage Effects in Low-Wage Areas,” IRLE Working Paper No. 106-19

- Marritz, N. and Elliot, K., “Getting Workers What They’re Owed,” Legal Aid Justice Center, Nov 2019

- Ibid.

- Goren, L., “The Crimes We Ignore,” The Commonwealth Institute, May 2015