August 6, 2020

Statewide PFML: A Critical Step Toward Racial, Economic, and Health Equity

Everyone should have the ability to take time away from work to care for themselves and loved ones without risking their financial stability. People who call Virginia home agree: a 2020 study found that 84% of registered voters in Virginia support a 12-week paid family and medical leave policy that all working people would be able to access. Virginia residents working for the federal government and, most recently, Fairfax County will soon have access to comprehensive paid family leave programs. Virginia as a whole should follow and improve this lead.

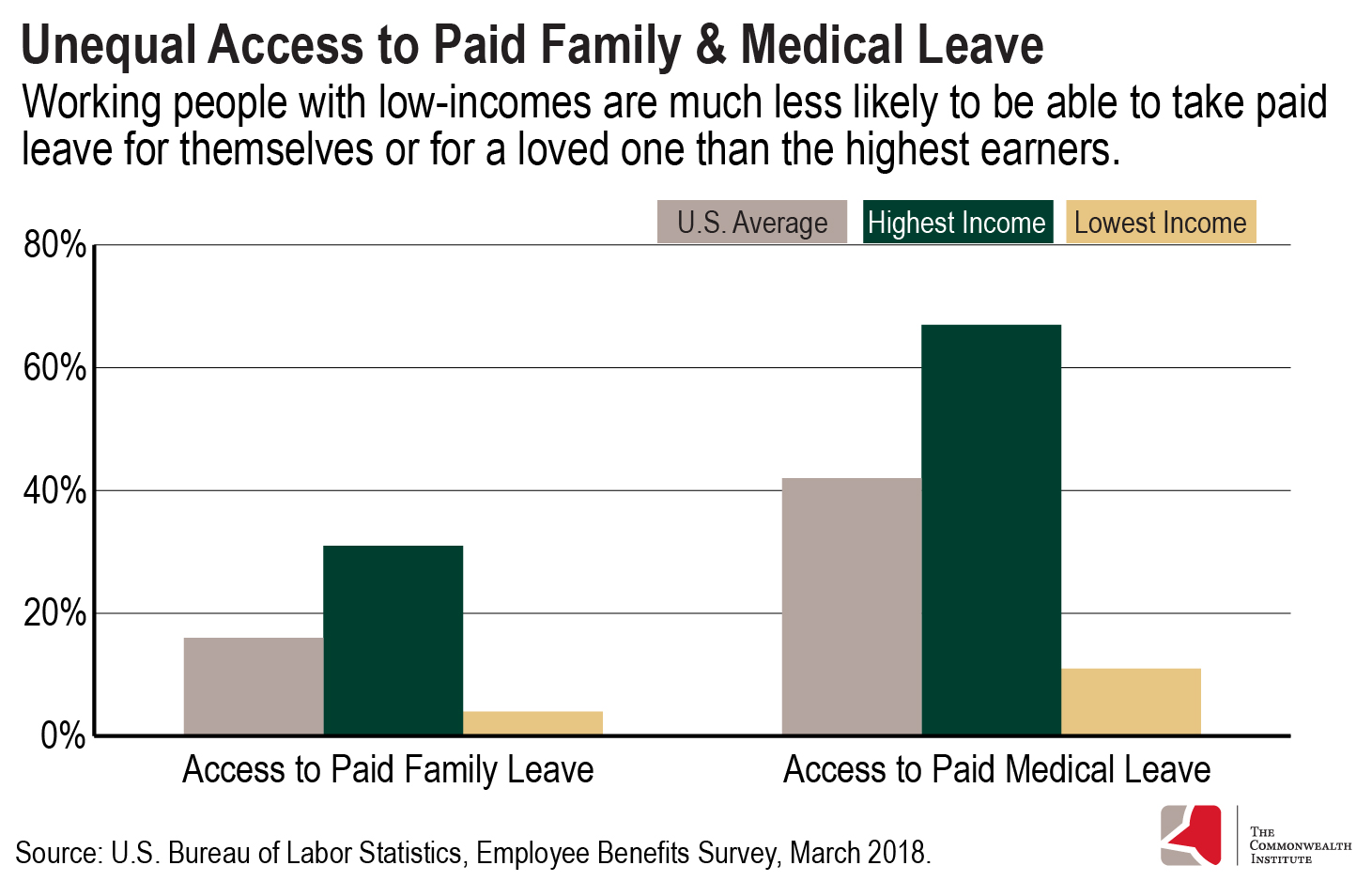

Currently, many workers rely on the policies of their employer in order to access paid family or medical leave. Unfortunately, the status quo means that, nationally, the highest wage workers are over 7 times more likely to have access to paid family leave and 6 times more likely to have access to paid medical leave in the form of short-term disability insurance, compared to the lowest wage workers.

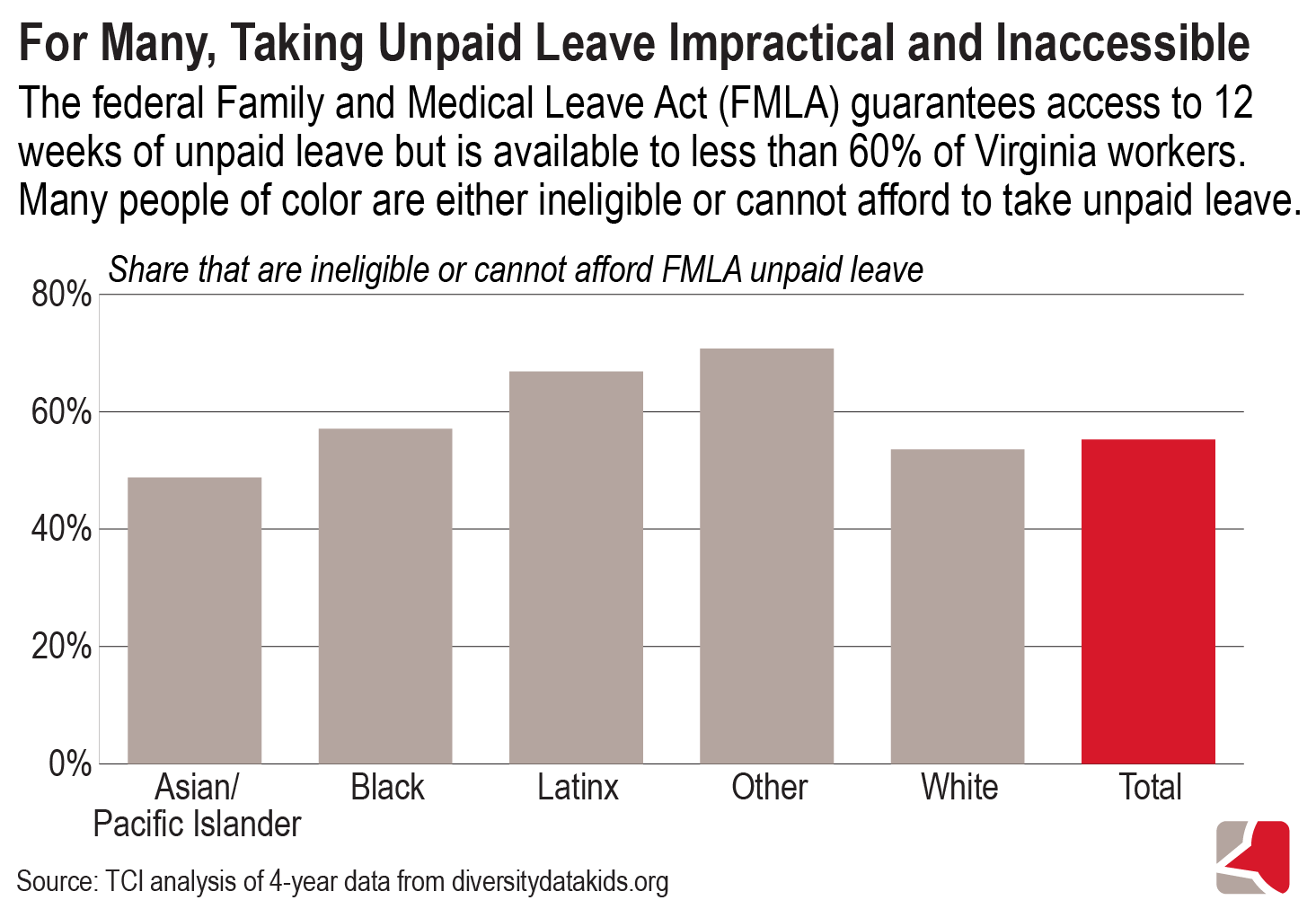

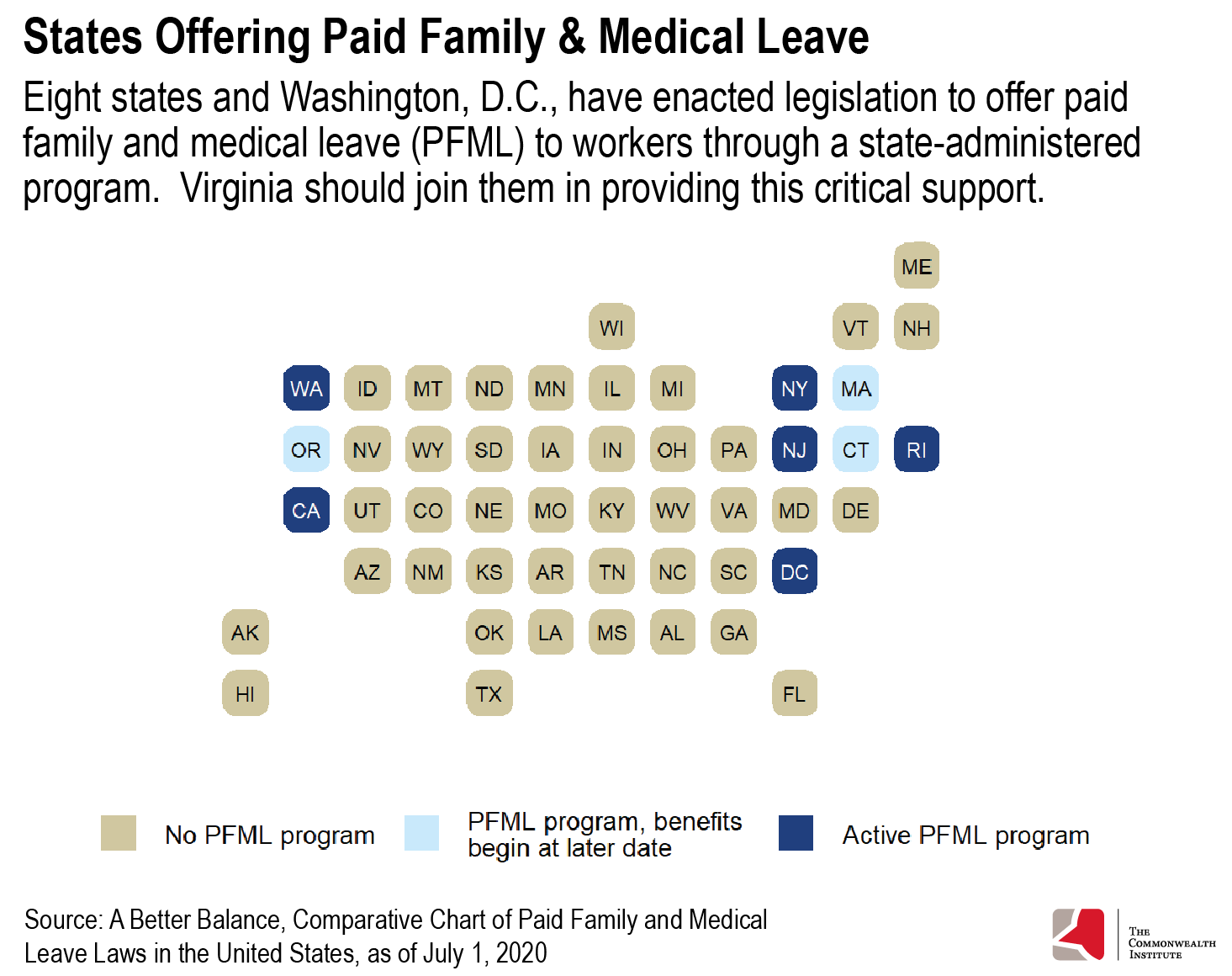

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) guarantees access to 12 weeks of unpaid leave but is only available to 60% of workers. This patchwork system of employer policies and FMLA currently leaves families with low incomes, people of color, and women of color at a severe disadvantage when making decisions about taking leave — forcing many to put the health and well-being of themselves or a loved one in direct competition with the ability to pay for basic needs. Working people in eight states either currently or will soon have access to a state-run paid family and medical leave policy that removes added financial stress during a serious health event.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of paid family and medical leave programs on public and individual health. While the federal government scrambled to design a temporary paid leave policy, it potentially excludes roughly 4 in 10 workers nationwide. States that have already implemented a state paid family and medical leave policy were best positioned to take immediate action to combat the spread of COVID-19 while helping many working people meet their basic needs.

Paid family and medical leave as has been proposed in Virginia would allow most workers to take up to a 12-week absence of work while still receiving partial wages. This leave could be used when welcoming a new child to a family through birth, adoption, or placement through foster care. The program could also be used to respond to a family member’s or a worker’s own serious health condition. A statewide paid family and medical leave proposal is different from a state paid sick day policy which would allow workers to accrue leave that they can use in order to take short leaves of absence — a day or two — to deal with smaller health issues. These two policies would work best in tandem with each other, helping working people address both short-term and long-term health concerns without fear of job or income loss.

While all caregivers are honored to be there for the ones we love, the job is overwhelming and often-times soul-crushing. We shouldn’t have the added burden of financial ruin — a burden that paid family medical leave could help avoid.

MELISSA ALEXANDER

Unequal Access to Paid Leave

A statewide paid family and medical leave program would allow more working people in Virginia the opportunity to take time off to care – time to care for themselves, a loved one, or a new addition to the family. Currently, many families with low incomes cannot afford to take advantage of the national Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). The policy only applies to 60% of workers and, while it allows people to take 12 weeks of time off without losing their job, there is no guarantee of any pay. For a family living paycheck to paycheck this is simply not an option.

Beyond the protections provided by FMLA, access to family and medical leave — especially leave that is paid — is even more limited. A recent survey found that only 16% of private sector employees in the U.S. have access to paid family leave, and only 42% have access to long-term paid medical leave through short-term disability insurance.

Lack of access to paid family and medical leave is particularly an issue among working people who are paid low wages. Across the country, only 4% of the lowest wage workers have access to paid family leave compared to 31% of the highest paid workers. Similarly, only 11% of the lowest wage workers have access to paid medical leave in the form of short-term disability insurance compared to 67% for the highest paid workers. Families who are most financially vulnerable do not have many options when it is time to care for themselves or a loved one.

PFML Would Help Families with Low Incomes Navigate Health and Financial Concerns

While some families may be able to accommodate the financial impact of temporarily losing a source of income, it is challenging for most. Nationally, 74% of workers live paycheck to paycheck. And it is estimated that 55% of Virginia families are unable to take advantage of unpaid leave entitled by FMLA because they do not qualify or cannot afford to. This financial reality adds another level of stress during a time of a serious health concern.

Access to paid leave is crucial for families with low wealth who may not have the resources to take extended unpaid time off. Families living paycheck to paycheck are often unable to save consistently and can be set back in their financial goals by car repairs, medical bills, and other unexpected costs. Preparing to live up to three months without income can be daunting to many when basic costs for living, such as rent, food, transportation, and utilities, will remain in place regardless of ability to work. The status quo forces too many working people to choose between their health or taking care of a loved one and paying for essentials like rent and food. No one should be forced to make that decision.

PFML Would Help Break Down Barriers Faced by Communities of Color

Due to historic and present-day barriers to wealth and economic mobility, Black and Latinx families tend to experience higher rates of poverty and are paid less than average, making unpaid leave impractical and inaccessible. In Virginia, 67% and 57% of Latinx and Black workers, respectively, are either ineligible or cannot afford to take unpaid leave through the protections provided by the FMLA leave. These structural, discriminatory barriers prevent families of color from being able to afford extended time off to care for themselves or their loved ones, which in turn puts their health and economic well-being in jeopardy.

A statewide program would also help to address a long history of racist policy choices, including exclusionary housing policies and barriers to health care, and discrimination that have put communities of color at heightened risk for health concerns. Research has found that people who are Black, Latinx, or American Indian tend to have chronic health conditions, such as asthma, at higher rates and at a younger age than their white counterparts. This can impact their ability to remain in the workforce and highlights the need for paid medical leave so that people are able to take the time off to care for themselves in order to return to work.

This policy could also protect the health of infants as paid leave has been strongly associated with fewer infant deaths (from birth to one year). In Virginia, Black families experience infant mortality at a rate of 10.1 in every 1,000 live births — twice as high as Latinx (4.4 in every 1,000 live births), white (4.8 in every 1,000 live births), and American Indian (4.6 in every 1,000 live births) families. The bottom line: a statewide paid family and medical leave program can give more families of color, particularly Black families, a healthier beginning and future.

For Women of Color, A State Family and Medical Leave Program is Critical

A paid family and medical leave policy would be especially vital for the health and financial security of women of color and their families.

Nationally, 74% of non-Hispanic Black mothers and 47% of Latinx mothers are key or sole breadwinners for their families, compared to 45% of non-Hispanic white mothers.

Being a key or sole breadwinner in the family is made more difficult by the fact that women of color are regularly paid much lower wages. On average, for every dollar that is paid to non-Hispanic white men, Latinx women are paid 54 cents, American Indian women are paid 57 cents, Black women are paid 62 cents, and Asian American women are paid 90 cents. And women of color take on significant caretaking responsibilities: households headed by a person of color are more likely to be multi-generational, and women in general tend to be the primary caregivers in their families. Leaving the workforce is often not an option, making the need for paid family and medical leave even more critical.

A paid family and medical leave program could also help address unequal maternal health outcomes for Black women. Nationally, Black women are 2.4 times more likely than white women to die during pregnancy or within one year of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management (this does not include accidental or incidental causes).

In Virginia, Black women are 1.9 times more likely to die using the same measure than their white counterparts. Paid leave also allows new mothers more time to attend important postpartum health visits, recover from childbirth, and bond with their child. A state paid family and medical leave program along with other targeted policies could help make sure that Black mothers have an equitable opportunity to survive childbirth.

The COVID-19 Pandemic Underscores Need For These Policies

The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the need for access to paid family and medical leave options for working people. The inability to take extended leave while maintaining income may have resulted in loss of employment or people struggling to make ends meet. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government implemented a paid sick program and a paid child care leave program through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). Yet this legislation left out people working for large businesses (500 or more employees) and excludes health care workers, emergency responders, and smaller businesses (fewer than 50 employees)) that apply for an exemption. Roughly 4 in 10 workers are potentially ineligible for the emergency sick leave program due to these exemptions, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. These policies are also time-limited and will only be in place until December 31, 2020.

Early data shows that states such as California and Rhode Island were able to respond to the pandemic using existing paid family and medical leave programs without needing to wait on federal intervention. Both states saw an increase in claims for medical reasons in March, showing the states’ increased ability to support working families during this difficult time. Additionally, Rhode Island was able to quickly adjust the rules of its paid family and medical leave program in order to meet the needs of its residents during the public health emergency. More work needs to be done in order to determine what impact these policies had on slowing the spread of COVID-19 in these states. It is clear, however, that working people in Virginia could have benefited from a permanent, more equitable, and comprehensive state paid family and medical leave program. These needs will continue long after temporary and insufficient federal policies expire.

PFML Legislation in Virginia and the United States

Bills were introduced during the 2020 legislative session (HB 825/SB 770) that would have implemented a 12-week paid leave program for all working people who meet the monetary minimums to qualify for state unemployment benefits, covering about 83% of Virginia’s civilian workforce. The proposals would have been funded through employer and employee contributions and would allow individuals to earn up to 80% of their weekly wages, not to exceed 80% of the average statewide weekly wage ($1,204). These proposals would allow more families with low incomes to take the necessary time off to care without having to worry about how they would meet their basic needs.

The estimated contribution rate for both employers and employees was estimated to be just 0.39% of earnings each for the first year, and all contributions would be held in a newly created “Family and Medical Leave Insurance Fund.” If an individual was earning $30,000 a year, for example, the employer and employee would each contribute roughly $2.25 a week. For an individual earning $50,000 a week, the employer and employee would each contribute $3.76 a week. This represents a relatively small investment for a large safety net.

There is growing interest and movement in state-run paid family and medical leave programs across the nation. Eight states and Washington, D.C. have either implemented or plan to implement a paid family and medical leave program. Many have passed laws and have rolled out their programs very recently. Washington, D.C. and Washington state both started paying out paid family and medical leave benefits during 2020. Three states — Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Oregon — will begin paying out benefits between 2021 and 2023. Virginia should join the leadership of other states in offering this necessary policy for all workers who call the state home.

Strengthening Virginia’s Legislative Proposals

In order to craft a program that works best for everyone in Virginia, recent legislation can be strengthened with additional language and program features. Virginia can look to states that have implemented programs or are planning to do so for guidance.

Any upcoming legislation can work to maximize benefits for working people with lower incomes who may not be well-positioned to take an extended leave at even 80% of their normal wages. This can be done by implementing a sliding scale wage replacement. Oregon plans to do this by providing 100% of wages up to 65% of the average statewide weekly salary ($715) and then half of earnings up to a maximum of 120% of the average statewide weekly salary ($1,320). The maximum amount of reimbursement would remain flat for everyone, but benefits would be targeted for those who need it most. See below for an example based on late 2019 Oregon data:

- Worker A ($31,200) earns $600 a week: would receive full paycheck during leave

- Worker B ($50,400) earns $969 a week: would recieve $842 a week during leave

- Worker C ($79,200) earns $1,523 a week: would receive $1,119 a week during leave

- Worker D ($120,000) earns $2,307 a week: would receive $1,320 a week during leave

Connecticut, Oregon, and Washington have added language entitling working parents to an additional two weeks of paid leave if they faced pregnancy-related health concerns. Adding a similar provision in Virginia can provide new families that are simultaneously welcoming a new child into their family and addressing health concerns an added buffer prior to coming back to the workforce.

Next Steps

Virginia lawmakers have recognized the need and growing interest in a state paid family and medical leave program and have included language in the state budget to form a work group. The budget states, “The Chief Workforce Development Advisor and Secretary of Commerce and Trade are hereby directed to study the development, implementation and costs of a statewide paid family and medical leave program for all employers.” This study is expected to present its findings by September 30, 2020.

As we await results and recommendations of this work group, working people in Virginia continue to navigate a patchwork of workplace leave and unpaid leave, or are simply forced to go to work during times of serious health concerns. Growing examples of successful programs across the nation and strong support here in Virginia position the state to be a leader in extending this important policy to people who live in the commonwealth. The 2020 special session and the 2021 legislative session provide an opportunity for lawmakers to listen to the needs of working families in Virginia and remove a financial barrier for families who need the time to care for themselves and their loved ones.