August 14, 2020

Budget Choices for Today and Tomorrow: Learning Lessons from the Great Recession and Setting Virginia on a More Equitable Path

Executive Summary

As Virginia policymakers prepare for a special session to address the state budget and policing reforms, this report provides background on the choices made by Virginia legislators during the last major recession, the continued impact of those choices, the potential impact of relying on cuts to new investments currently “frozen” that were first passed during the 2020 regular legislative session, and a menu of budget options for legislators as they move forward.

Key findings include:

- During the Great Recession and its aftermath, seemingly across-the-board cuts particularly harmed low-income families and communities. For example, cuts to state support for K-12 schools most harmed children in low-income communities where the schools rely mainly on state support for K-12 education and where local governments have the least ability to make up for state funding cuts with local revenue. And because the cuts were structural changes to the state school funding formula, many have not been fully reversed even 11 years after the depth of the recession.

- Policy barriers to health coverage and lack of paid family and medical leave have particularly harmed communities of color and have left Virginia less prepared to face the current pandemic. While expanding Medicaid was an important step forward, more needs to be done to make sure every person in Virginia can access health care services when needed.

- The budget items that were frozen (“unallotted”) during the April reconvened session are initiatives that express the priorities of the new legislative majorities and many take important steps to remove barriers facing low-income families and communities of color. Balancing the budget by removing funding for almost all new initiatives rather than taking a more holistic and balanced approach to closing the budget gap, policymakers would be undoing much of the important progress toward a more equitable Virginia that was made during the 2020 legislative session.

- State policymakers have a variety of options to move Virginia forward during the special session and regular 2021 legislative session, including fully using available federal funds and raising new revenue by closing loopholes and asking wealthy individuals and corporations to pay their fair share to meet the immediate needs of families and communities.

Introduction

COVID-19 and the current recession create real challenges for Virginia’s families, communities, and the commonwealth as a whole. The latest reports indicate that Virginia finished the most recent budget year that ended June 30 (fiscal year 2020) with about $236.5 million less general fund revenue than expected, and revenue for the current budget year (fiscal year 2021) is also likely to be lower than expected when legislators initially passed the budget in March. While this moment is unique due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Virginia has faced deep revenue holes before. Choices made during the last recession offer a mix of positive and negative lessons for today’s policymakers.

By meeting these challenges with thoughtful consideration, smart choices, and hope for a better future, Virginia policymakers have the opportunity to protect critical services, invest for tomorrow, and set the state on a more equitable path. As policymakers consider how to address the health, economic, and fiscal damage of the COVID-19 crisis, it is worth reviewing the impact of the choices made during the last recession, how Virginia’s current path to balance the budget primarily by “unallotting” new initiatives will harm families and communities, and the opportunities state policymakers have to take a more holistic approach and set the stage for an equitable recovery. The budget is a fundamental policy document that indicates who and what we prioritize as a state — it is time to make sure it reflects the needs of everyone who calls Virginia home.

Lessons for Virginia Policymakers from the Great Recession

During the Great Recession, general fund (GF) revenues dropped 14% between fiscal year (FY) 2007 and FY 2010 after adjusting for inflation. While policymakers tried to protect critical services for struggling families and core services by using accounting gimmicks, underfunding the state retirement funds, and drawing from revenue reserves to make ends meet, they still made deep cuts to important services such as K-12 education. And by cutting support for local governments and public universities, state policymakers effectively passed down deficits and tough choices to Virginia’s students, families, and local governments.

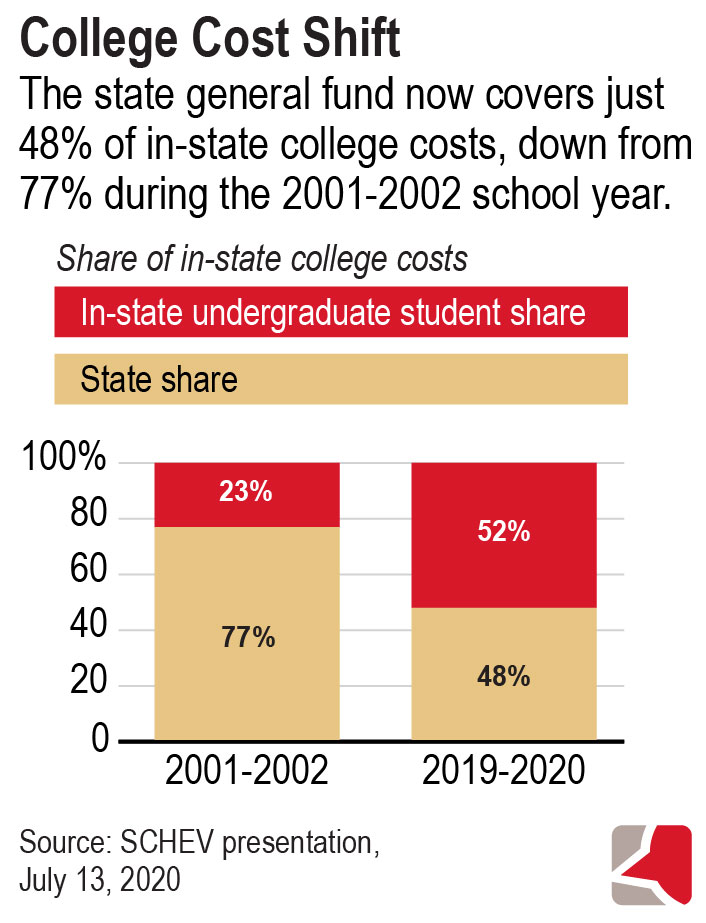

For example, Virginia’s college students and their families have faced sharp increases in tuition as the state covers a smaller share of in-state tuition than in past years. On average, the state GF covered just 48% of the cost of an in-state undergraduate education during the 2019-2020 school year, down from 77% during the 2001-2002 school year (the last year before significant state funding cuts in the wake of the 2001 recession).

And even as local revenues from property taxes were falling during the Great Recession, legislators reduced support for services carried out by local governments such as local libraries and mental health services for children and youth. These reductions totaled $50 million in FY 2010, $60 million in FY 2011, $60 million in FY 2012, and $50 million in FY 2013 (these amounts are the across-the-board reductions as reported by the Virginia Department of Planning and Budget and do not include cuts to state support for public education).

These choices created additional challenges in the aftermath of the official recession as Virginia struggled with the impact of federal budget cuts on the state’s economy. While this may appear inevitable, policymakers could have chosen to use a more balanced approach, including raising new revenue, to meet the needs of Virginia

families and communities.

Seemingly Subtle Changes to School Funding Can Cause Long-Lasting Harm

K-12 education is a particularly stark example of the long-term harm that can be caused by not taking a balanced approach that includes new revenue. Even during the most recently completed budget year, more than 10 years after the official end of the Great Recession, state per pupil support for K-12 education had not been restored to pre-recession levels after adjusting for inflation.

There are three key lessons from the last recession on how state cuts impacted school funding.

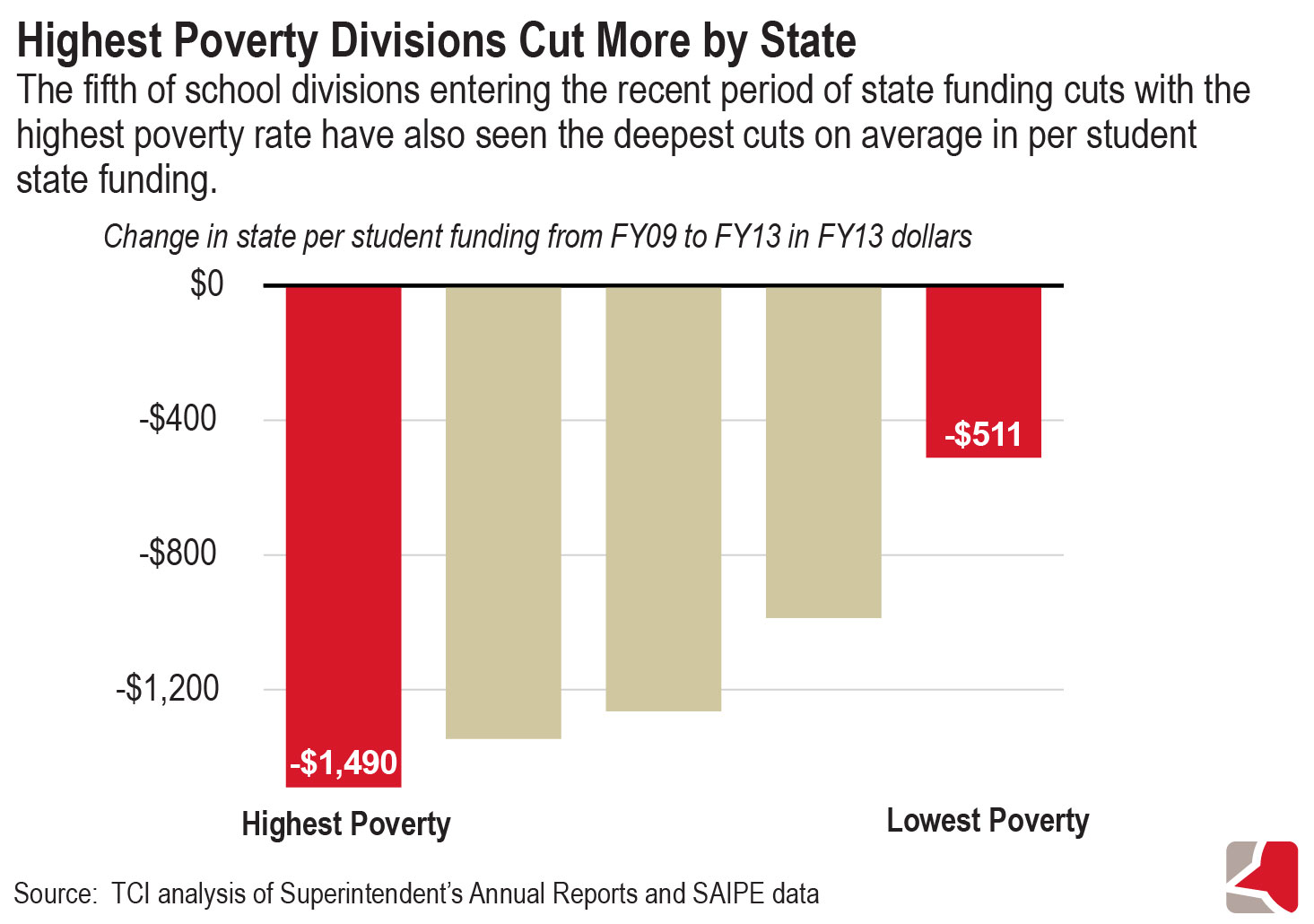

Schools in highest poverty communities hit hardest

State funding cuts during the last recession hit the highest poverty school divisions almost three times harder than the lowest poverty school divisions. This happened in part because high-poverty communities have less local wealth and rely more heavily on state resources to fund their school systems. Per capita property values in Lee County, for example, are almost one-eighth what they are in Arlington County. When low-wealth communities see larger state cuts, they are more limited in their ability to respond. This has also had a disproportionate impact on Virginia’s schools with the most students of color. Support staffing decreases were four times larger in divisions with the highest percentage of students of color compared to school divisions with the highest share of white students.

Structural cuts stayed in place after recovery

The structural nature of the cuts made last recession has kept them in place on a permanent basis. The support staff cap, like many of the cuts made in the last recession, were not one-off solutions that would automatically be removed when the economy recovered. Instead, they were permanent changes to Virginia’s primary school aid formula, the Standards of Quality, that requires lawmakers to go into the formula and remove it. A UVA student succinctly made this point when testifying before the Virginia Board of Education as they last voted on the support cap: “It is not a temporary solution to current economic hardships. Instead, it is a permanent reduction in the Standards of Quality, which will outlast the current recession.” We cannot afford to make that same mistake again for another generation of students.

Low point occurred after federal aid ran out

The worst of the funding cuts for K-12 education did not occur in 2009 when the national economy was at its lowest point. Instead, the low point occurred years later in the 2011-2012 school year after the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds went away and the state had not taken sufficient action to generate new revenues to fill the gap. This problem was compounded by simultaneous federal austerity measures that reduced revenue for federal contractors located in Virginia, causing a new round of revenue challenges soon after federal recovery funds ran out.

The fact that Virginia’s K-12 funding has been unable to recover from cuts made more than a decade ago shows just how damaging and long lasting austerity measures can be during a recession. It is critical that state leaders recognize the harm caused by the choices of past governors and General Assembly members and choose a different path in responding to the impacts of this crisis.

Failing to Fully Draw Down Available Federal Aid Harmed Families and Communities

During the Great Recession, federal policymakers provided a range of economic and fiscal supports to help state policymakers maintain critical services and help families get back on their feet. This support helped Virginia balance its budget, especially in the early years of the recession, yet Virginia policymakers left some help on the table. For example, Virginia failed to make improvements to its unemployment insurance system that would have resulted in new federal dollars to cover both the direct service costs and administrative improvements.

Similarly, the refusal by Virginia policymakers to implement Medicaid expansion until 2019 meant that, for five calendar years, Virginia legislators needed to use state GF dollars to cover critical health services for uninsured people who would otherwise have had health insurance through Medicaid. As a result, there was less money available to reinvest in K-12 education and other public services.

As a first step to setting a new path for a new future, Virginia must make use of all federal resources to protect K-12 education and other critical services. As a second step, the state will need to intervene and generate revenues of its own in order to protect families, schools, and communities in the years that follow, by asking wealthy Virginians and big corporations most able to afford it to pay their fair share.

Past Policy Choices Have Made Current Challenges Harder; Policymakers Can Take a New Path

Just as policy choices to reduce support for education, rather than raise new revenue, have caused long-term harm to public schools and families, past choices by Virginia legislators to under-invest in health care and erect barriers to health coverage have made it harder for families and communities during the current health and economic crisis caused by COVID-19. The vote by legislators in 2018 to expand Medicaid coverage was a step in the right direction to make sure more people in Virginia have access to health care, but there is more to be done.

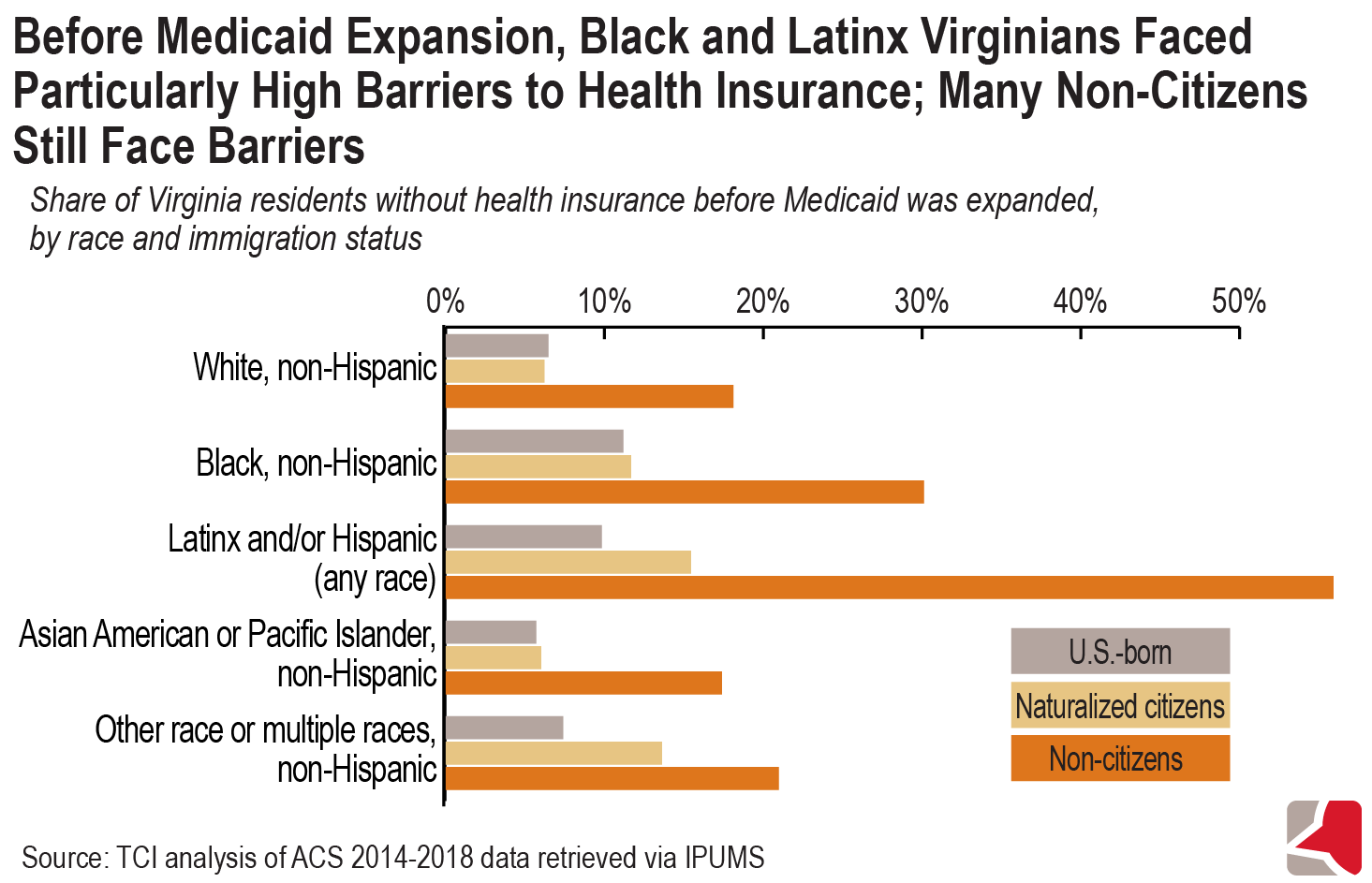

Inequities in health care coverage and access have made Black and Latinx individuals more likely to contract COVID-19 and Black individuals more likely to face complications that result in hospitalization. In 2018, before Medicaid was expanded, roughly 12% of all adults under the age of 65 were uninsured in Virginia. Yet when you consider uninsured rates by race, we see that 32% of Latinx adults, 16% of American Indian adults, 15% of Black adults, 12% of adults identified as mixed race or “other” race, 9% of white adults, and 8% of Asian American adults lacked health insurance. Lack of coverage, along with other social factors that impact health, could increase the fear of getting tested or receiving treatment for COVID-19 due to the potential for high out-of-pocket costs, and increase the chances for community spread.

These differences in health care coverage and other socio-economic factors mean that people of color often have a greater number of complicating health factors than their white counterparts.

Medicaid coverage expansion is helping, but too many are still left out

Virginia has taken some positive steps in recent years to increase access to affordable and comprehensive health coverage. Over 441,000 adults across Virginia are currently enrolled in health coverage thanks to the decision to expand Medicaid in 2018. The impact of Medicaid expansion on health coverage for communities of color is not yet fully understood due to a two-year lag in Census data and the absence of enrollment statistics broken out by race/ethnicity by Virginia’s Department of Medical Assistance Services. Yet it is likely, based on pre-expansion projections, that Black Virginians — who previously were less likely than Virginians as a whole to have health coverage — have particularly benefited from the reduced barrier to Medicaid coverage.

However, non-citizens in Virginia — 86% of whom identify as Latinx, Black, Asian, or Other/Mixed Race — continue to face obstacles in obtaining health coverage. Over half (52%) of undocumented immigrants in Virginia are uninsured and have no access to public health insurance programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, or the Childrens Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Undocumented immigrants are also ineligible for subsidized health coverage on the ACA marketplace, further limiting low-cost health coverage options.

Virginia is also one of just six states with an obscure rule that creates an obstacle for lawfully present immigrants to access Medicaid coverage. In the commonwealth, lawfully present immigrants must establish a 40-quarter (10 year) work history, concurrent with the federal five year requirement, before qualifying for Medicaid. Language and funding to eliminate this barrier was included in the General Assembly-approved state budget in March, but has been “unallotted” until it can be reconsidered during special session.

Lack of paid family and medical leave and paid sick leave

During the early stages of the pandemic, Virginia’s low-wage workers may have been unable to take time off to deal with symptoms and access treatment related to COVID-19. Paid sick days were largely unavailable to most low-wage workers. Nationally, only 31% of the lowest-wage workers have access to paid sick days compared to 94% of the highest paid workers.

Paid medical leave to cover an extended time off is even less available to working people who are paid low wages. Only 11% of the lowest-wage workers across the country have access to paid medical leave in the form of short-term disability insurance compared to 67% for the highest paid workers. The lack of access to paid sick days and paid extended leave have likely contributed to higher levels of community spread, as people needed to continue working and not risk losing income. Low-wage workers (9.2%) are also six times less likely to be able to work remotely compared to higher wage workers (61.5%), which could increase low-wage workers’ exposure to COVID-19.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government implemented a paid sick program and a paid child care leave program through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). Yet this legislation left out people working for large businesses (500 or more employees), and excludes health care workers, emergency responders, and smaller businesses (fewer than 50 employees) that apply for an exemption. Roughly 4 in 10 workers are potentially ineligible for the emergency sick leave program due to these exemptions, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. These policies are also time-limited and will only be in place until December 31, 2020.

Each year since 2018, proposals to implement a paid family and medical leave (PFML) program in Virginia have been considered but have not passed the General Assembly. The PFML legislation proposed in 2020 would have implemented a 12-week paid leave program for all working people who meet the monetary minimums to qualify for state unemployment benefits, which is about 83% of Virginia’s civilian workforce. This program paired with a paid sick day mandate — proposed during the 2020 legislative session — could have allowed more workers to take needed precautions without being pressured by financial factors to go to work.

Early data shows that states such as California and Rhode Island were able to respond to the pandemic using existing paid family and medical leave programs without needing to wait on federal intervention. Both states saw an increase in claims for medical reasons in March, which highlights the states’ increased ability to support working families during this difficult time. Additionally, Rhode Island was able to quickly adjust the rules of its paid family and medical leave program in order to meet the needs of its residents during the public health emergency.

More work needs to be done in order to determine what impact these policies had on slowing the spread of COVID-19 in these states. It is clear, however, that working people in Virginia could have benefited from a permanent, more equitable, and comprehensive state paid family and medical leave program. The need for an inclusive program existed before the pandemic and will continue long after temporary and insufficient federal policies expire.

Virginia’s Current Path of Cutting New Investments Threatens to Halt Progress

During the regular legislative session in early 2020, Virginia policymakers used the budget to make a number of important policy choices to address past wrongs and invest in a new future. Unfortunately, when the extent of the pandemic and recession became clear during the spring, legislators accepted the “unallotment” of almost all of these new investments, rather than taking a more comprehensive look at budget priorities or a more balanced approach that includes new revenue. Because the new fiscal year began on July 1, these “unallotments” already mean that important new investments are going unmade and the needs of people in Virginia are going unmet. For example, the “unallotment” of funding to remove the “40 quarters” barrier means there are immigrant Virginians without access to health coverage who would otherwise have comprehensive coverage through Medicaid. During the upcoming special session, policymakers can and should act to undo the harm of the unallotments and instead take a holistic approach to balancing the budget.

During the upcoming special session, policymakers can and should act to undo the harm of the unallottments and instead take a holistic approach to balancing the budget.

Halting Health Care Initiatives Reduces Access When it is Most Needed

Restoring funding to unallotted health care budget items could help Virginia better respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and avoid exacerbating inequities in health coverage and outcomes. Pressing pause on funding associated with approved policies also means a pause in the implementation of these policies. Unless the governor takes a form of executive action, these policies cannot go into effect until funds are potentially restored during the special legislative session.

A budget item that has direct implications for pandemic response is the elimination of the “40 quarter rule” ($4.5 million). This rule effectively bars many lawful permanent residents from enrolling in Medicaid until they can prove 10 years of employment in the United States (some people can use the work history of a spouse or parent to qualify). Gov. Northam and the General Assembly have already indicated that eliminating this barrier is the right choice by initially including it in the budget. Access to comprehensive health coverage is vital for families and individuals at all times and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Extending health coverage for new mothers with incomes between 138% and 205% of the federal poverty level from 60 days postpartum to 12 months ($3.2 million) is another policy that could ensure continuous health coverage for individuals with low incomes. Currently, Medicaid/CHIP for pregnant women ends 60 days after a birth for women whose income is too high to qualify for traditional Medicaid coverage and yet, experts agree that the risks associated with childbirth often extend long after 60 days. The opportunity for a healthy start for new families is crucial in setting up a healthy future for children in the commonwealth.

Policies such as comprehensive adult dental benefits ($34.0 million), voluntary home visiting programs for new parents ($11.8 million), and investments in behavioral health infrastructure through STEP-VA ($49.9 million) will all be vital in order to make sure that health equity in Virginia does not regress in the aftermath of the pandemic. The budget decisions that state lawmakers make in the near future will have long-term impacts on the well-being of families across the state. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted major, long-standing health inequities in Black, Latinx, and immigrant communities. Investments must be made during this difficult time in order to signal a commitment to fixing these issues.

Unallotting New K-12 Education Halts Important Steps Toward Equity

As with the lessons from budget cuts during the last recession, the unallotments to K-12 education serve as a particularly key example of the harm caused by the current path and the positive changes that could be made by a new approach.

The governor and General Assembly have unallotted $490 million in early education and K-12 funding for the General Assembly to act on in the special session. The unallotted funds include a substantial increase to Virginia’s At-Risk Add-On program ($61.3 million), which directs resources to school divisions with the highest concentration of students from low-income families. Other unallotted investments include resources for the Virginia Preschool Initiative ($91.5 million) and increasing students’ access to school meals ($10.6 million). These investments aim to strengthen support for the very students who have long-faced barriers to a high-quality education and who will be most impacted by the missed educational opportunities resulting from the current crisis.

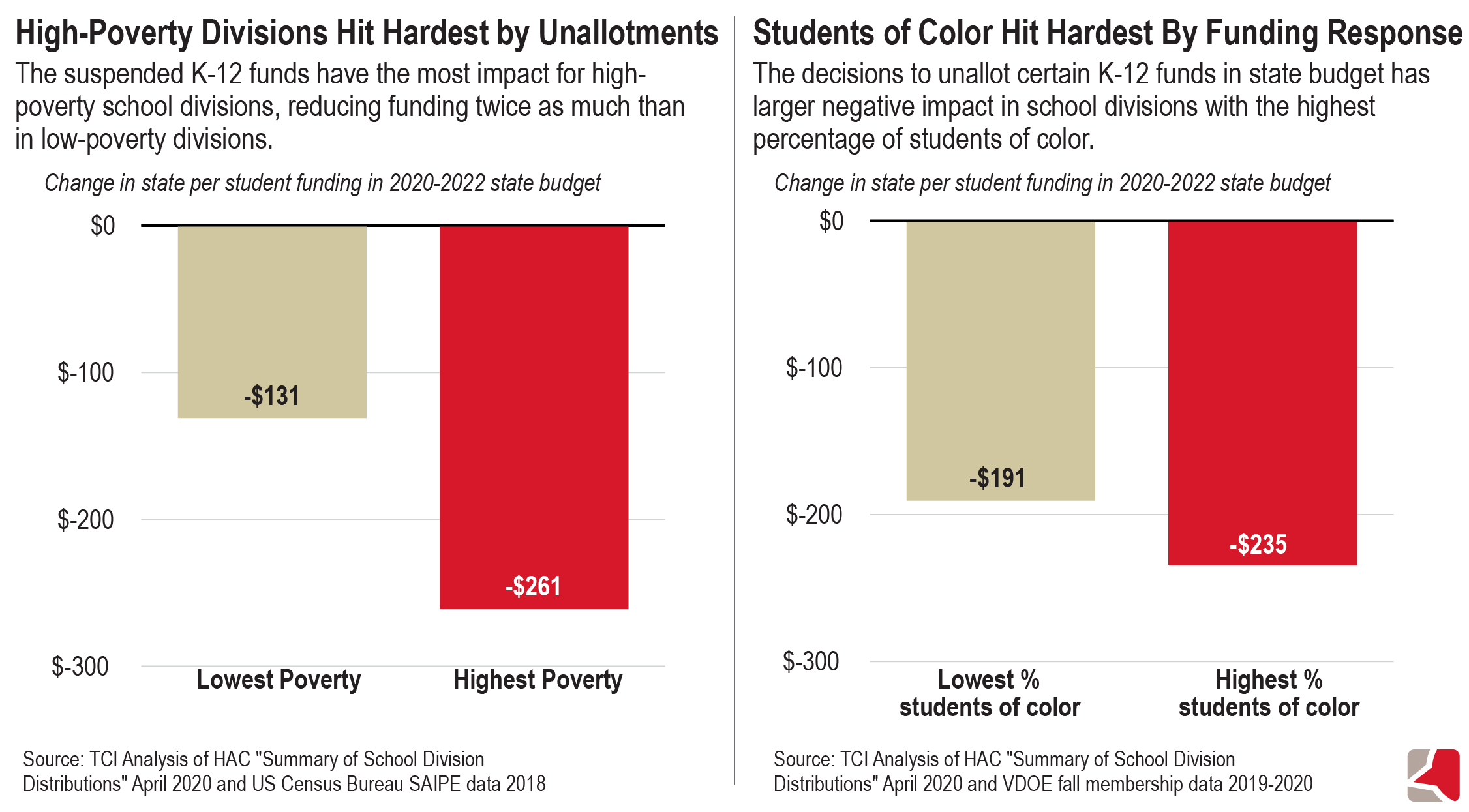

The highest-poverty divisions will be hardest hit by the unallotments. In fact, the suspended funds for school divisions with the highest child poverty rates are twice as large per student as they are for the lowest-poverty school divisions — $261 per student compared to $131. School divisions with the highest child poverty rates include Petersburg, Colonial Beach, Danville, and Richmond City.

There are similar impacts for school divisions with the largest shares of students of color. Divisions with the highest percentage of students of color will lose out on 23% more per student than school divisions with the lowest percentage of students of color — $235 per student compared to $191 — across the biennium. School divisions with the highest percentage of students of color include Petersburg, Manassas, Franklin City, and Richmond City.

Affordable Housing Initiatives Are At Risk

The loss of jobs and income for many families due to the COVID-19 pandemic has sharply increased the number of families at risk of losing their homes nationally, with one study estimating that houselessness could rise 40-45% by the end of the year. Black and Latinx families are most at risk of eviction. This is due to both past and present discrimination leading to lower incomes and lower wealth, as well as direct discrimination on the part of landlords. Researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University’s RVA EvictionLab found that in Richmond City, “neighborhood racial composition is a significant factor in determining eviction rates, even after controlling for income, property value, and other characteristics,” with more evictions in neighborhoods with more Black residents and fewer evictions in neighborhoods with more non-Hispanic white residents.

Although Virginia-specific data on the current housing situation is limited, it is unlikely that the commonwealth is exempt from the recent trend of increasing housing instability, particularly with several Virginia cities having high eviction rates in the past and many Virginia families facing high housing costs compared to the maximum amount of unemployment benefits that are available. The national EvictionLab found that, in 2016, the Virginia statewide eviction judgement rate was 5.1%, more than double the national rate of 2.3%, and the eviction filing rate in Virginia was also more than twice the national rate. Richmond, Hampton, Newport News, and Norfolk — all cities where at least 40% of residents are Black — had particularly high rates. As of July 26, there were 9,441 unlawful detainer (eviction) hearings scheduled in Virginia between that date and September 14.

The use by Virginia of some of the flexible funding for states in the CARES Act for housing assistance, including eviction and foreclosure prevention, is a good step, yet at the same time policymakers are considering cuts to investments in affordable housing that were made during the regular legislative session. Unallotted funds for housing that are at risk of being cut if policymakers do not take a holistic, balanced approach include $46.0 million of support for the Housing Trust Fund, $25.6 million in funding for permanent supportive housing, and $8.6 million for eviction defense/diversion and affordable housing pilot programs.

Higher Education Reductions Will Reduce Financial Aid, Despite Likely Increased Need

Support for college and university students in the form of financial aid and incentives to freeze tuition and fees was also hard-hit by the April 2020 unallotments of new initiatives, including but not limited to the freezing of proposed increases in financial aid ($60.6 million), eliminating the new G3 program that would have provided assistance with community college tuition for some low- and moderate-income students ($71.0 million), eliminating tuition moderation incentives ($79.8 million), and and eliminating additional support for students with high financial need who attend Virginia’s two historically Black public universities ($17.0 million). These cuts are likely to make it harder for students from low- and moderate-income families to afford an advanced education just as the benefits of a “professional” job that can be done from home become more starkly clear. Additionally, these cuts come at a time when the need for financial aid is likely to increase due to students and their families losing employment income.

Virginia Has the Opportunity to Do Better

Virginia has an opportunity to avoid repeating the mistakes made during previous recessions. State policymakers can choose to adopt a more balanced approach that involves drawing upon state reserve funds, fully using federal stimulus funds, and generating new revenues. Together, these tools will help the state better navigate this crisis and maintain our commitment to investing in communities, in part by preventing cuts to critical public investments, including in areas that already faced funding challenges before the pandemic.

Smart use of reserves and short-term budget tools

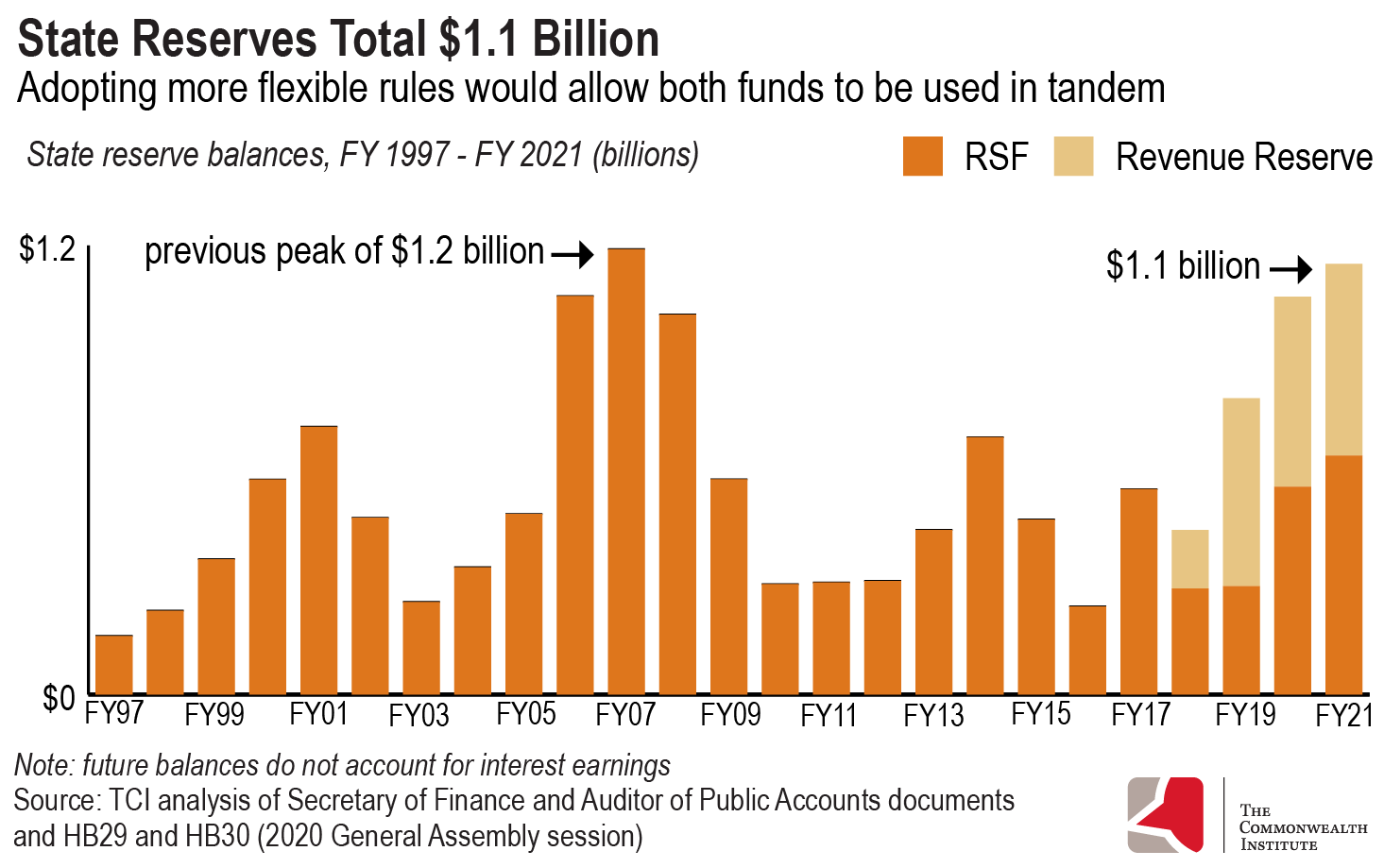

State rainy day funds are one of the important tools that state governments have to respond to revenue shortfalls. Similar to other states, Virginia makes deposits into its rainy day fund — formally known as the Revenue Stabilization Fund (RSF) — during periods of economic expansion and then is able to draw upon these funds when economic conditions unexpectedly worsen. Transfers from the RSF to the state general fund (GF) during and just after the last recession played a key role in helping to balance the state budget.

Despite economic growth nationally, the state also made withdrawals from the RSF during a four-year period of revenue challenges (FY 2015 through FY 2018), which likely reflected the effects of federal budget sequestration on Virginia. To increase the availability of state reserves beyond constitutionally-required deposits into the RSF, lawmakers created and began making deposits into a new Revenue Reserve Fund in 2017.

As of FY 2019, the balance in the Revenue Reserve totaled about $500 million, while the balance of the RSF will total about $630 million in FY 2021 after the next constitutionally-required deposit.

However, under current law, the Revenue Reserve is generally not able to be used in tandem with the RSF and is not accessible when the state faces a large revenue shortfall. The RSF is available when a downward revision to the GF revenue forecast compared to GF revenue appropriations is greater than 2% of prior-year revenues, while in general, the Revenue Reserve is available when a downward revision results in a projected revenue shortfall that represents 2% or less of prior-year revenues. State law also grants additional authority to the governor during a state of emergency, which allows additional spending from state funds for “disaster service missions and responsibilities.” A budget amendment or other legislative change will need to be adopted to maximize the effectiveness of state reserves in the current crisis by granting policymakers broader discretion to address general revenue shortfalls.

This kind of additional flexibility for the revenue reserve could provide up to about $850 million in additional resources across two fiscal years if revenue declines from the reforecasting process exceed 2% of prior-year revenues. According to both national and state experts, large state revenue shortfalls are expected, which will likely exceed the 2% threshold. This change would build upon actions already taken by the governor and General Assembly to remove or unallot $900 million in planned Revenue Reserve deposits.

Fully using federal funds

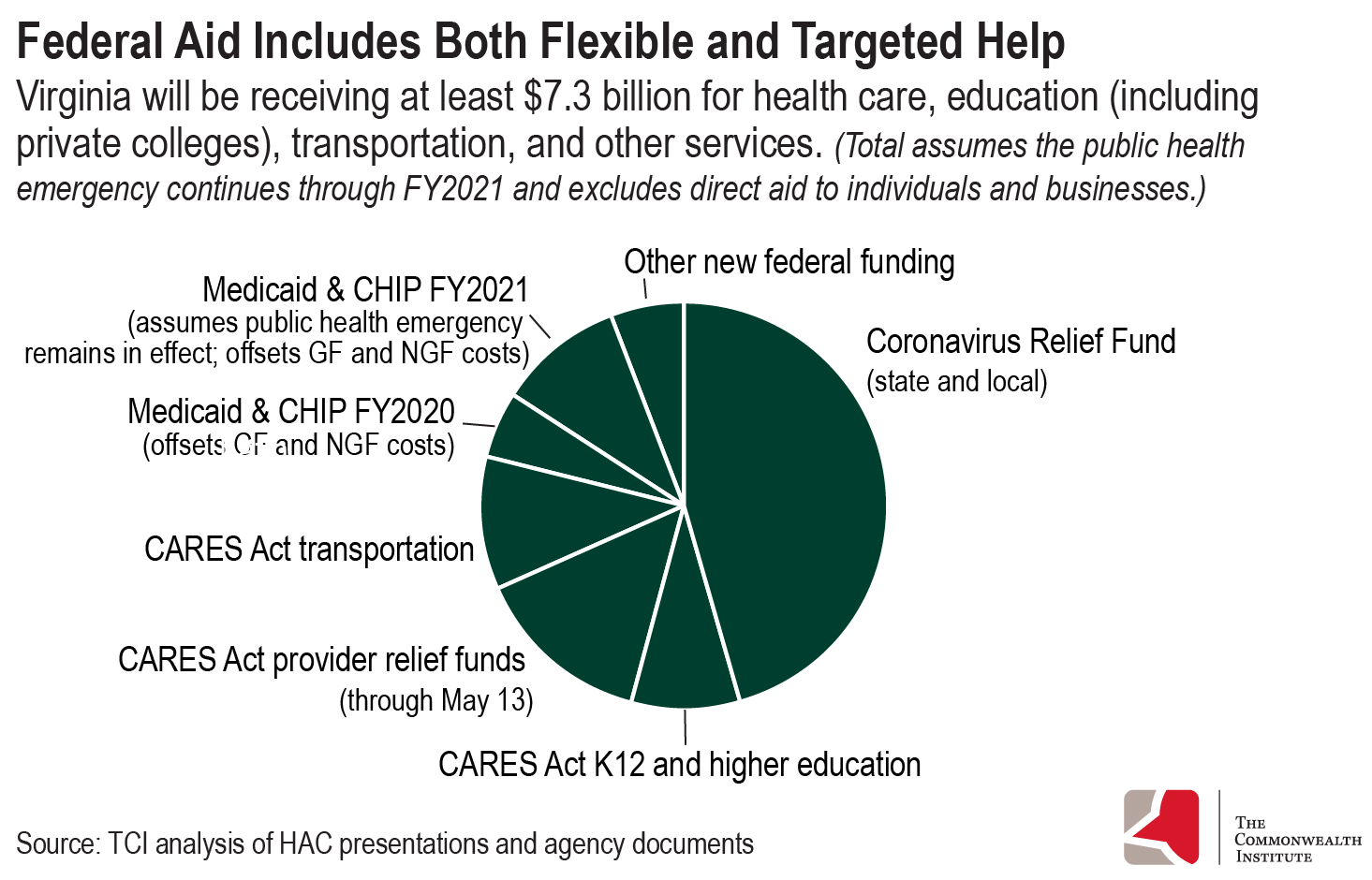

Several federal laws have passed in recent months to help address the health and economic impacts of the pandemic, and the federal government is currently considering additional measures that are needed to address the severity of the revenue shortfalls facing state and local governments. State policymakers should fully use these federal funds, both to fund the front-line health and human services spending that the state and local governments have undertaken and to respond to the significant impacts on families, communities, and businesses.

The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided Virginia with about $3.1 billion in direct fiscal aid from the Coronavirus Relief Fund, as well as additional education-specific aid from the Education Stabilization Fund. Localities with populations that exceed 500,000 also qualified for direct aid through the Coronavirus Relief Fund. In Virginia, only Fairfax County meets this threshold and will receive about $200 million in aid through the fund. State officials provided about $645 million in fiscal aid to Virginia’s cities and counties through the state’s share of the fund and have promised another $645 million in aid to local governments. The remaining amount is available for state investments.

Virginia policymakers should consider the best ways to spend these funds in a manner that is consistent with the statutory language and subsequent guidance from the U.S. Treasury Department. In addition to using these funds to directly support state efforts around the medical and public health response, the Treasury Department has indicated that these funds can be used for other “necessary expenditures” related to the pandemic. For example, payroll expenses for public safety, public health, health care, human services, and similar employees would be considered eligible due to their new roles in directly responding to the pandemic. Funds can also be used to provide “hazard pay” for essential workers and to establish direct grant and other rent and mortgage relief programs aimed at preventing evictions, foreclosures, and homelessness. An array of actions are considered permissible expenditures from the fund. The state response should prioritize those uses that direct greater support to the families and communities who are feeling the most significant impacts — and in many cases are either fully or partly excluded from the federal response to date.

The CARES Act also established the Education Stabilization Fund, which provides federal funds to states to support K-12 schools and institutions of higher education.

Virginia will receive $238.6 million from the Fund’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. From this amount, 90% is provided directly to local school divisions based on their Title I, Part A funding from the most recent fiscal year. The Virginia Department Of Education (VDOE) will receive the remaining 10% of the funds, which VDOE states will be used to expand distance learning by increasing technology access and developing resources for students, families, and educators.

In addition, Virginia will also receive $66.8 million as part of the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund. The state can award these resources to local school divisions or higher education institutions that have been most impacted by COVID-19 to provide emergency support and other education-related entities to provide emergency educational services.

The Fund also established the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, which provides funding directly to institutions of higher education. Virginia’s public and private institutions will receive about $294.4 million from this fund. These allocations are largely based on the institutions’ share of full-time students who receive Pell Grants. At least 50% of these funds must be provided to students for emergency financial grants related to expenses due to the pandemic’s “disruption of campus operations.”

The federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act also included federal assistance in the form of a 6.2 percentage point increase in the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for all states, including Virginia. This increase is effective beginning January 2020 and will last through the quarter in which the public health emergency declared by the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services for COVID-19 has ended.

The state Department of Medical Assistance Services estimates that the increased match will result in state GF savings related to traditional Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), totaling $319 million in FY 2020. The state Department of Social Services also estimated savings of $5.6 million in FY 2020 related to certain foster care and adoption programs. The state will receive additional savings during at least part of FY 2021. State lawmakers can use these savings to offset the budget impact of increased usage of health care and other public services.

While the federal assistance in CARES provides critical support, it falls far short of what is needed by state and local governments to adequately fund critical public services during this pandemic. The House, Senate, and White House may negotiate another much-needed stimulus package that, in addition to extending vital services such as federal unemployment insurance, may also include additional assistance for state and local budgets to provide health care services and help cover reopening costs for schools.

In addition, Virginia policymakers should make sure to pursue all options for federal funding as opportunities present themselves. For example, the governor and General Assembly agreed to establish a new work-sharing program, which will receive 100% federal matching funds through the end of this year as part of the CARES Act.

New revenues

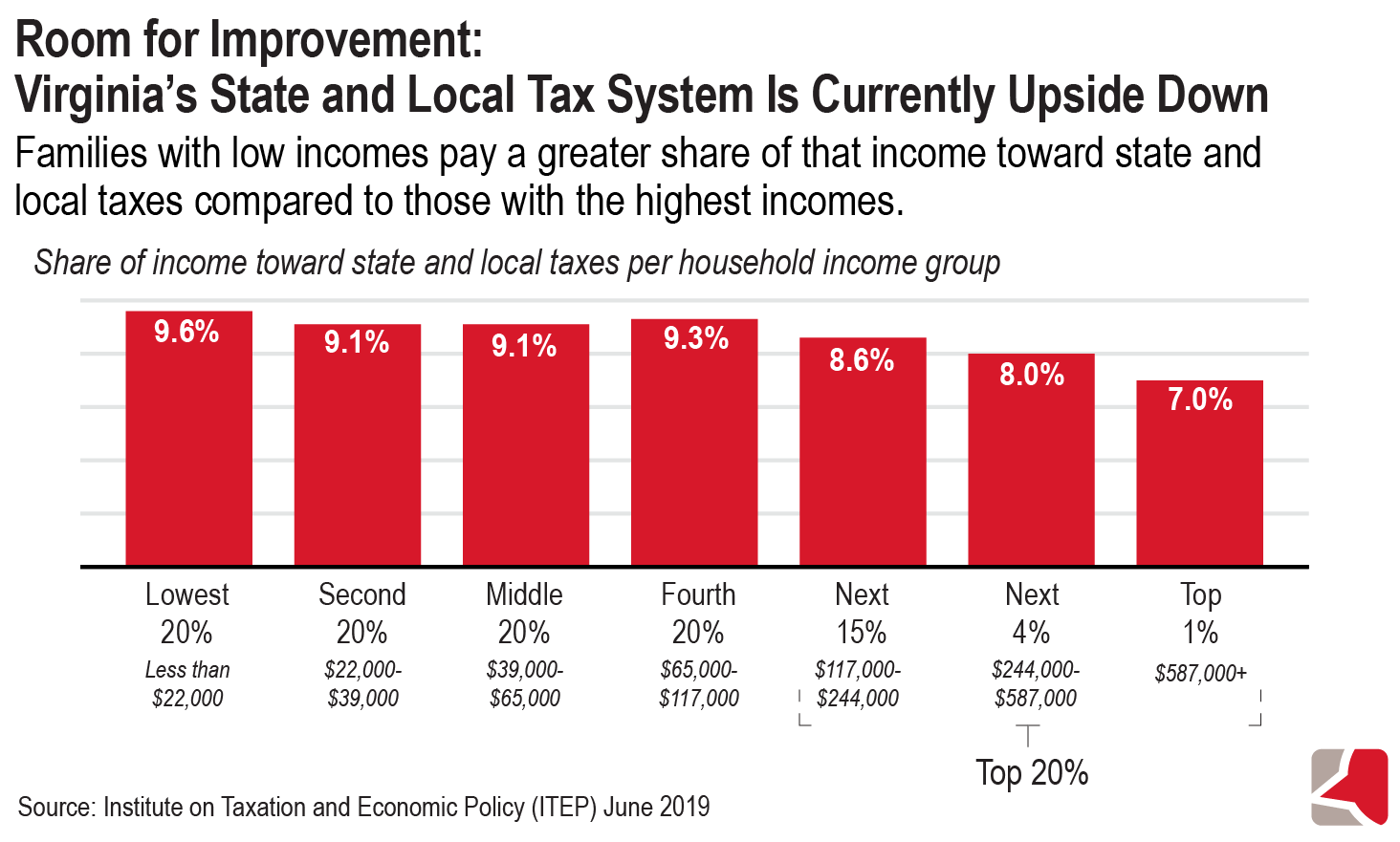

Virginia’s outdated revenue system has long kept the state from adequately investing in critical public services such as education. As state policymakers plan for likely revenue shortfalls in the near term, the governor and General Assembly should consider potential revenue options to help address some of these challenges.

With more and more of the economy shifting online, taking steps to modernize Virginia’s sales tax would better align the state revenue system with today’s economy and consumer spending patterns. State sales tax laws, including in Virginia, were written several decades ago and unintentionally exempt categories of goods that did not exist at the time. In particular, Virginia remains among the minority of states that generally exempt digital downloads and services from state taxation. About 30 states, plus Washington, D.C., generally tax digital products and services, including neighboring states North Carolina and Tennessee.

Taxing these products puts them on a level playing field with equivalent goods that have been traditionally included in sales tax bases like books and physical audio and visual media. During the 2018 General Assembly session, a bill to apply Virginia’s sales tax to digital products was estimated to increase GF revenues in FY 2021 and FY 2022 by $19.6 million and $20.6 million, respectively.

Virginia also allows certain retailers to retain a portion of their sales tax collections. Before the last recession, this program was much broader and had a larger revenue impact. However, since July 2010, a provision in the state budget has limited the program only to retailers that are not required to remit sales tax collections electronically (those with average monthly sales and use tax liability of $20,000 or below). Fully eliminating this program for that remaining group of retailers would increase GF revenues by about $12.8 million in FY 2021 and $13.1 million in FY 2022.

A large but often overlooked area of state budgets is “tax expenditures,” like special credits and other tax breaks. In recent years, Virginia policymakers have placed limits around certain tax credits to minimize their budget impacts, including the Land Preservation Tax Credit. Beginning in taxable year 2015, the state limited taxpayers to a maximum $20,000 per year for this credit. This limit expired at the beginning of this year. Restoring and extending this cap would preserve about $6.6 million per year.

Cleaning up our tax code by closing loopholes and asking wealthy Virginians to pay their fair share will allow for more resources in both the near and long term. Going forward, state policymakers should consider more comprehensive changes to the state’s tax system. For example, the state’s individual income tax uses an overall rate and bracket structure that was put in place in 1987. Virginia’s top individual rate of 5.75% begins at taxable income above $17,000. With the top rate starting at such a low level of income, the system does not reflect income changes that have occurred over

the past several decades and the higher ability to pay among the highest-income households. Creating new top rates for households with the highest incomes could generate additional resources for investments.

For example, adding new brackets beginning at taxable incomes above $100,000, $500,000, and $1 million and applying rates of 6.5%, 7.5%, and 8.5%, respectively, would generate about $998 million per year. This would affect few taxpayers in the state.

State lawmakers should also adopt needed reforms to the state’s corporate income tax system. During the 2020 General Assembly session, multiple bills were considered to enact one such reform — known as “mandatory combined reporting” — to address common corporate tax avoidance strategies. Updated state tax laws in this area could help to make sure large corporations pay their fair share in taxes and allow the state to invest more in critical state priorities.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 health crisis has disrupted life in Virginia and created enormous health and economic challenges, particularly for communities of color. The economic effects of the pandemic will likely last for years, but the severity of those impacts is not inevitable. With the right mix of investments and budget decisions, state policymakers can help Virginia meet these crises and fulfill its commitment to providing critical services. Fundamentally, that means avoiding the worst mistakes of the past. Under a more balanced approach, Virginia can use federal resources, state reserves, and new revenues, and limit the size and duration of any cuts so that our state is not set back another decade. Especially in this environment, policy that particularly advances the well-being of families with low incomes and communities of color must move forward.

Get the Report (pdf)

Read the release (pdf)